Sasha Yamada

University of Hawaiʻi, Mānoa

Freshman, Electrical Engineering

Expected Graduation: May 2019

Host Lab in Japan: Iwasa Lab, University of Tokyo

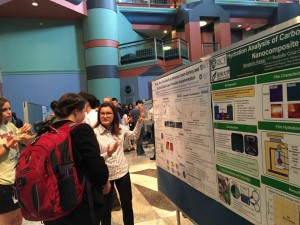

Research Project Abstract and Poster: MoSe2 Thin-Film Growth by Molecular Beam Epitaxy and Electrical Double Layer Transistor Implementation ![]()

Why Nakatani RIES?

What was originally just the subject of an email sent to every student in my school’s engineering department, is now my highly anticipated plan for summer 2016. After reading the description of the Nakatani RIES Program, I knew that I had to apply. The program matched my academic and professional goals very well and offered me an opportunity to better connect with my Japanese heritage. I plan to continue my education by going to graduate school and would like to continue to do research work in the future. As a student just finishing my second semester of college, the Nakatani RIES Fellowship allows me to have an international research experience that I would not be able to get otherwise. I believe that the Nakatani RIES Program will greatly benefit my engineering skills and help me to be successful in my ambitions.

I am most excited to work in my host laboratory and learn Japanese in an environment of immersion. I find the work being done in the Iwasa Lab at the University of Tokyo to be very interesting, and see parallels between their work with electrochemistry and aspects of the research that I have been doing at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. The Nakatani RIES Program offers an incredible opportunity to undergraduate physics and engineering students nationwide as it supports early exposure to research work and encourages international collaboration.

Goals for the Summer

- Gain meaningful research experiences that I can apply to the research I do at my home university

- Become conversationally proficient in Japanese

- Experience and personally connect with my Japanese heritage

Meaning of Nakatani RIES Fellowship – Post-Program

The Nakatani RIES Fellowship Program is a unique and formative experience for undergraduate students. Having such early exposure to advanced research allows students to build confidence in their abilities as scientists and engineers and start thinking about graduate school early. Being immersed in Japanese language and culture for 12 weeks is another distinctive feature of the program that makes the overall experience so impactful. You also have access to an extensive support network to ensure your success in the lab and in Japan in general. It encourages adventure and independence, and is overall the most incredible way to spend a summer.

Research Internship Overview

Over the summer I worked on 2D materials research in the Iwasa Lab. I was pretty unfamiliar with my research topic prior to my internship, but discovered that I really like the field and want to further pursue this area of research. One of my goals for the summer was to “gain meaningful research experiences that I could apply to the research I do at my home university.” I developed a lot of soft skills that I can apply to my UH research, but the technical skills that I learned don’t carry over as much. However, they are still very valuable, especially if I decide to focus on material science in the future.

I really enjoyed the environment of the Iwasa Lab. Everyone is very hardworking. The hours can be a little extreme, but everyone has got a good sense of humor. Iwasa-sensei is very involved in the lab and is a fun professor to work with. I got a lot of help from my mentor, as well as the other students in the lab. It’s a very supportive environment, and if you’re willing to work hard, you can do a lot.

Daily Life in Japan

My daily life in Japan was very research-centered. I would wake up and do my 40-minute commute by train to lab to get there by 10 am. At lab I’d either wait for my mentor to decide what we were working on that day or do some self-directed task to prepare for the experiment if I knew what we were doing ahead of time. I got lunch with the PhD students at around 12 pm almost every day, and almost invariably ordered shoyu ramen and tofu. After lunch, we’d go back to the lab and do more work until 6 pm, which was dinner time. We’d then go to either the cafeteria again or a close-by restaurant. After dinner we’d return to our experiments and I’d usually leave lab between 9 or 10.

I spent a lot of Saturdays in lab–for meetings and to get extra work done– so I mostly stayed in the Tokyo-area during the weekends. After my Saturday meetings and on Sundays, I’d usually go sightseeing with other Nakatani students. I saw a lot of places in Tokyo and in some of the surrounding areas like Yokohama and Kamakura. I also got to re-visit places that I liked a lot, like Sensoji in Asakusa, which I visited on four separate occasions.

My favorite experience in Japan was… getting lost and wandering around with other Nakatani students when we weren’t on a tight schedule. It’s fun to explore the less tourist-y parts of Japan.

Before I left for Japan I wish I had… organized which places I wanted to visit better.

While I was in Japan I wish I had… visited Tsukiji Fish Market! I put off going until it was too late. Make sure you get your ‘Japan bucket list’ done early.

Excerpts from Sasha’s Weekly Reports

- Week 01: Arrival in Japan

- Week 02: Trip to Akita

- Week 03: Noticing Similarities, Noticing Differences

- Week 04: First Week at Research Lab

- Week 05: Critical Incident Analysis – Life in Japan

- Week 06: Preparation for Mid-Program Meeting

- Week 07: Overview of Mid-Program Meeting & Research Host Lab Visit

- Week 08: Research in Japan vs. Research in the U.S.

- Week 09: Reflections on Japanese Language Learning

- Week 10: Interview with a Japanese Researcher

- Week 11: Critical Incident Analysis – In the Lab

- Week 12: Final Week at Research Lab

- Week 13: Final Report

- Tips for Future Participants

Week 01: Arrival in Japan

After one week in Japan, there were a few things that stood out to me about Japanese society. The first is that it is very efficient. The Tokyo metro system, which on a map looks like someone let a kindergartner go wild with a box of crayons, is extremely efficient. Trains are never late. The boarding process is always fast. The maps in the subways are easy to read, even as a foreigner. Strangers sit down next to strangers and all seats get filled. In the United States, people hate to sit down next to strangers and nearly avoid it at all costs. Sometimes there will even be empty seats on a crowded bus so that people can avoid sitting next to each other. This doesn’t happen in Japan. Everyone goes about their own business, generally unconcerned about the other passengers– unless of course they’re fourteen loud American students ruining the peaceful environment of their daily commute, which brings me to my next topic: hyperconsciousness of your effect on those around you.

We were warned at the Houston orientation about being loud. Americans are loud; it’s a fact. Fourteen American college students let loose in Tokyo are even louder. In the subway cars we very quickly become the center of attention, subject to glares of annoyance from the other passengers. I try to talk as softly as possible when riding public transportation, but it is especially hard to keep fourteen people talking at an appropriate volume when everyone is excited. Hopefully we can get better at this because I don’t like negative attention that we’ve been attracting.

We were also told that everyone in Japan dresses nicely, but I was still thrown off guard by just how nicely everyone dresses. Every morning when we walk to our language classes we’re surrounded by a sea of full suits and high heels, making our sneakers and t-shirts look overly casual. I even felt under-dressed wearing an outfit that I wore to a poster session at my home university. There are also big stylistic differences between Japanese fashion and what I’m used to seeing in Hawaii. Everyone in Hawaii dresses very casually, and generally not-so-modestly. The clothing in Japan is a lot less form-fitting. There are lots of very wide-legged pants for women, and I haven’t seen anyone wear particularly tight-fitting shirts. (And definitely no Hawaii-standard shorts!) Japanese fashion even seems to be a visual manifestation of the culture– formal and modest.

Something that was also interesting to me was that to the Japanese students from the KIP program, I not only act, but look very foreign, despite being half-Japanese. I grew up in a town with practically no other Japanese kids, so being half-Japanese there had automatically labeled me as Japanese. At the University of Hawaii at Mānoa there are lots of local Japanese students and I’m also frequently grouped in that category. But in Japan, I’m not. The only clue to my Japanese descent is my last name, “Yamada.” I was asked if I was Spanish, French, and even Greek. I thought it was a funny contrast of how much perception of race changes depending where you are.

Language Courses

I was originally assigned to be in a language class by myself, but have been joined by 3 other students in the past week. I definitely prefer to have others in the class because the first day felt like a three-hour oral exam. It’s more intimidating to have a one-on-one class.

I feel that the language courses are very effective because a lot of what we cover is directly applicable to our daily lives. We learn vocabulary and sentence structures that we can use in a realistic setting. I would prefer if we went more in depth with grammatical structure, but I understand that it’s more of a crash course in survival Japanese than a traditional language class. I’ve been trying to use Japanese as frequently as possible to retain what we learn.

Japanese Culture & Society Seminar

The first week of the Intro to Japanese Culture & Society seminars and activities included a lecture by Packard-sensei about cultural differences between America and Japan, a discussion about the American presidential election with the KIP students, a visit to the Edo-Tokyo Museum, and tickets to a sumo match.

It was insightful to hear the opinions of the KIP students about American politics. One of the major topics that we discussed was the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). I had previously heard of TPP, but didn’t have more than a basic understanding of it. I was surprised to hear that it was such a big issue for Japan because it had received such a small part of the American election media coverage. I hadn’t really thought about the implications for Japan of the United States not supporting the TPP. Discussing politics with the Japanese students was informative because it offered a different perspective and raised questions that I hadn’t thought of.

I thought that visiting the Edo-Tokyo Museum was very informative about Tokyo’s history. I was impressed by the intricacies of the exhibits and thought that the interactive displays were fun to try. Going to a sumo match was really interesting. After Packard-san explained to us that each move that the sumo wrestlers make before the round starts is religiously motivated, I watched the matches with a different perspective. It was fascinating to see how Shintoism tied into so much of the event. I was also intrigued by the sponsorships of the matches and would like to know more about what the motivation is for companies to sponsor the matches.

Question of the Week

Japan is one of the safest places I’ve ever been to. What makes Japan so safe?

Science & Engineering Lectures & Lab Tours

This week we only had one science & engineering lecture, which was done by Professor Kono, and we did lab tours at the University of Tokyo. I really enjoyed touring the labs at the University of Tokyo. It was one of the highlights of my week. All of the projects that we saw were so impressive, especially the biomedical robots. It was inspiring to see the work that was being done there and made me very excited for my research internship.

I thought that Professor Kono’s lecture was very informative, but it was a little hard for me to follow. I haven’t taken many technical courses so it was a little overwhelming to go from “What’s a conductor?” to quantum mechanics in under three hours. However, after going through my notes again, I think that it provided good exposure to a lot of the concepts that we are going to be working with. It made me wish that I had more technical knowledge so I could’ve followed it better. It gave me an idea of what I need to look further into to prepare for my internship.

Initial Research Project Overview

The material that I will be working with is a transition metal dichalcogenide (TMD). Transition metal dichalcogenides are 2D semiconductor materials with atomically thin monolayers. Their properties can be drastically changed by manipulating the material electrically or electrochemically using electrical double layer (EDL) techniques. I will be working on the growth and characterization of TMDs using molecular beam epitaxy (MBE).

Paper Summary

I read and reviewed “Electrostatic and electrochemical tuning of superconductivity in two-dimensional NbSe2 crystals“.

Purpose: Achieve electrostatic and electrochemical tuning of superconductivity in 2D NbSe2 Crystals.

Background: 2D transition metal dichalcogenides (TMD) are direct band gap semiconductors. Their electrical properties can be drastically altered by modifying their thickness. Past research has confirmed that decreasing the thickness of the TMD, NbSe2, also decreases the superconducting critical temperature (Tc). For this material specifically, modification of the band structure has been experimentally confirmed, making it a good choice for this study.

Method: The first step was to check the bulk properties of a NbSe2 single crystal. This showed that the resistivity was temperature dependent. The superconducting transition appeared at 7.3 K. The next step was to fabricate electrical double layer transistors (EDLTs) of various thicknesses (bulk, 7-nm, 3-nm) for ultrathin NbSe2 crystals. This was done by mechanical exfoliation of the bulk single crystal onto a silicon dioxide substrate. Electron-beam lithography was used to make the pattern for four-probe electrodes, in which titanium and gold were later deposited into. Silicon dioxide was then deposited onto the electrodes to prevent exposure to the ionic liquid required for the EDLT’s operation. The thicknesses were confirmed by using an atomic force microscope. To test for electrostatic tuning, the VG was applied at 210 K in a vacuum and then the sample was cooled to 170 K and purged with helium. It was then cooled to 1.8 K. Electrochemical tuning was tested by decreasing VG from 0V to -2V in a vacuum and then cooling the sample to 1.8 K, rewarming it to 210 K, and then applying VG from 0V to -3V. This process was repeated 10 times.

Results: From the electrostatic tuning tests there was a clear trend that a reduction in the thickness of the material drove down the superconducting critical temperature. It was also observed from the electrochemical tuning tests that the sheet resistance had a larger change the higher VG was applied. For each cycle of the procedure there was a monotonic increase in the sheet resistance, indicating that an electrochemical process had occurred. These findings are promising because they suggest that the ionic liquid gating technique used in the EDLT can be used on any layered superconductor to create an ultrathin 2D superconductor. This allows for more flexibility in the design and fabrication of ultrathin superconductors.

Week 02: Trip to Akita

When we got off the shinkansen, the differences between Akita and Tokyo were immediately apparent. The station we arrived at was small and quiet. It was in a residential area with small houses and local restaurants. There were no flashy advertisements or aggressive taxi cars, just simple houses, the JR station, and a highway.

As we drove further into the countryside the houses became spaced farther apart, making room for rice fields and forests. Mountains covered in pines rolled past the car window, speckled with yellow farm machinery. Windy roads were flanked by pines as tall as the buildings in Tokyo. We were surrounded by the natural beauty of Japan.

One of my favorite parts of the weekend trip was visiting Lake Tazawa, the deepest lake in Japan. It was the largest lake I’ve ever seen; I would’ve believed it was part of the Pacific Ocean if I hadn’t been able to see the mountains on the other side. The water was calm and clear and the view was absolutely breathtaking. The scenery in Akita reminded me a lot of Pom Poko, a Studio Ghibli movie. Pom Poko draws on folklore about raccoons having shapeshifting powers and follows their quest to stop the development of their home. There was a statue of a raccoon and fox at the lake, which I thought was a funny coincidence.

When we visited Omagari Agricultural High School I was really impressed with the students’ research presentation. They did research on neutralizing Tazawa Lake by various chemical means (buffering systems, electrochemistry, etc). Not only was the material advanced for high school sophomores, but I was impressed by their commitment to the environment. They were trying to make a difference in their community, and were doing a very good job at it.

The people in Akita were very kind to us and eager to share their prefecture’s specialties. They were excited to have us try Akita pickles, which have a smoky taste, and Akita ice cream, which is shaped like a rose. And of course, we had lots of Akita rice. The president of the ryokan we stayed in was very accommodating and personally attended multiple activities of ours. This enthusiasm about Akita’s specialties was very apparent during our discussion about economic revitalization in Akita. The topic soon became how to increase tourism in Akita, to show more people what it has to offer.

Week Two Overview

During the second week of orientation we visited the National Museum of Nature and Science, had a discussion with the KIP students about Artificial Intelligence, and tried taiko drumming. The taiko drumming was especially fun to try as a group and was one of the highlights of my week. The language courses became more challenging last week when we were introduced to more vocabulary and verb conjugations, but they are still very manageable. We’ve gotten past learning absolute survival Japanese and beginning to learn how to express more complex thoughts. It’s really interesting!

Question of the Week

After seeing the difference between Akita and Toyko, how drastic are other regional differences?

- There are eight official regions in Japan and 47 prefectures and, similar to states in the U.S., each is quite proud of its own uniqueness. Each region will have its own history, traditions, and cuisines. What’s nice is when you visit a specific area of Japan there will always be some special food item or treat that is unique to that region and that you should try. It’s also important to keep in mind that the Japan we know today was not always one cohesive country and Japanese history is full of many shifts in power, seats/capitals of government, and rule by competing warring clans. The regional differences aren’t just about geography or cuisine, they also have grounding in the history and transformation of Japan over time. Here’s a humorous take on the history of Japan, in just a 9 minute video.

Intro to Science & Engineering Seminars Overview

This week we had several science & engineering lectures by Professor Stanton from the University of Florida, Prof. Otsuji from Tohoku University, and Prof. Ishioka from NIMS. Lecture topics included terahertz technology, semiconductor nanostructures, and fermisecond spectroscopy.

I really appreciated Prof. Ishioka’s lecture that commented on the gender disparity of college graduates in Japan and tied in her own personal experience working as a woman scientist. The gender disparity in Japan is very concerning, but it’s also apparent in American universities (especially for my major, electrical engineering). Her comments were very insightful.

The technical lectures were easier to follow this week, as some of the material that Professor Stanton was very similar to what Professor Kono had covered. I thought that Prof. Otsuji’s Pachinko analogy was a really creative and effective way of explaining quantum states.

I have also been doing independent studying as well to get more out of the technical lectures.

Week 03: Noticing Similarities, Noticing Differences

The Unspoken Rules of Tokyo Transportation

- Occupy as little space as possible.

Tokyo is a very efficient city. Part of that efficiency involves cramming as many people as you comfortably (I’m using this word loosely) can in buses, metro cars, and trains. It’s nice in the way that you can always get where you need to go, no matter what time of day. However, it can make you feel very claustrophobic if you have a long ride on a crowded train.

I also noticed a weird double-standard to this rule for elevators. At the Sanuki Club hotel, and even in the office building where we had our Japanese language classes, some people would get very annoyed when we would all try to cram into an elevator with them. Many people would wait for the next one to come, and some would push through us and storm out of the elevator all together. I’m not entirely sure what the reason for this is. Maybe it has something to do with the noisiness that usually accompanied us.

- Do not interrupt the flow of people.

Metro stations, like many places in Japan, have a ritual for entering and exiting. There may not be a water purification station, like at the shrines, but there is a definite routine that everyone follows. Step one: Have your Passmo/Suica card ready before you’re in line to enter the station, and make sure you have sufficient funds for your trip. Step two: Know where you’re going, and join the crowd that moves like a school of fish to your desired line. Step three: Wait in line in front of the car you plan to board. Step four: When your metro does arrive, let others out of the car before you enter. Step 5: If it’s crowded, wiggle your way through so that others can board as well. If it’s not crowded, you may stand or take any open seat.

- Absolutely no loud noises.

Phones are fine, headphones are fine, quiet conversations with a friend are fine. However, if you are being loud, be it laughing, talking, or anything else, you will attract other passengers’ attention, and not in a good way.

- Do not start conversations with people you don’t know.

I actually really like this rule, it’s practical. One of the reasons why I avoid using

public transportation at home is because I’ve had too many strange people try to talk to me on buses. (Buses in Hawaii are notorious for bizarre intoxicated passengers, many of them being homeless.)

I feel that one of the reasons why public transportation works so well in Japan is that people use it for what it is, and only that: transportation. Metro cars aren’t a place to chat or eat lunch. They’re not a place to make new friends. They’re a way for you to get from one place to another, so everyone goes about their own business.

- You should give up your seat for people who need it more (the elderly, disabled, etc.), although I haven’t seen anyone else do this yet.

Japanese society is known for its politeness, to the point where people circumvent saying “no” as much as possible. This value doesn’t seem to directly translate into public transportation courtesy. I haven’t seen anyone give up their seat for an elderly or disabled person yet. I’ve also heard Packard-san complaining about young people never giving up their seats on trains, despite the signage that asks them to. This was very surprising to hear, especially because of the cultural idea that one is supposed to respect their elders.

On the buses in Hawaii, almost anyone will give up their seat for an elderly or disabled person, the bus driver might even ask you to if you don’t. When I was on a crowded JR train to Kamakura, I instinctively stood up when I saw an older couple get on. They seemed shocked that someone got up to let them sit down. It’s a memory that stuck with me because of how thankful they acted about something that to me seemed like a common courtesy.

Week Three Orientation Program Overview

For the third week of orientation we had lectures by Shimizu-sensei, from Rice University’s Department of History, and Packard-san about Japanese history and culture, as well as a discussion with the KIP students about bioethics. We finished up our last week of Japanese classes and said goodbye to our great AJALT teachers. It was full of goodbyes and the anticipation of new beginnings.

We were inspired by Shimizu-sensei’s talk and saw a Japanese baseball game on Saturday. It was the Swallows vs. the Buffalos. I was very amused to learn that one of the star players on the Swallows is also a Yamada. It was funny to see my last name on a giant red flag and being chanted by half a stadium, “Yamada-san! Yamada-san!” when he went up to bat. It was also cute and strange to me that baseball fans cheered with tiny umbrellas. That was definitely different from all of the American baseball games I’ve been to, where you’re not even allowed to take normal umbrellas into some stadiums.

A few other students and I also saw an act of a kabuki play. I was really impressed by the striking visual and sound effects. Due to my limited Japanese ability and the characteristic way kabuki actors speak, it was near impossible for me to understand the dialogue. However, I was able to follow what was going on from just watching, so it wasn’t a problem. It was an incredible performance.

Before we knew it, the week was over, and we all parted ways. It’s still hard for me to believe that the first three weeks went by so quickly.

Intro to Science & Engineering Seminar

For the final week of orientation, we had lectures by Professor Bird, Professor Aoki, and Dr. Lyons from the National Science Foundation. The technical lectures were focused on semiconductor bandgap engineering and scanning probe microscopy. Dr. Lyon’s lecture was focused on the role of students in international scientific collaboration. All of these lectures raised questions and gave answers that helped me prepare for the start of my internship.

I found Professor Bird’s lectures, from the University at Buffalo, to be incredibly helpful to understanding some of the concepts in the research papers published by my host lab. A couple of the previous lectures we had introduced the concepts of bandgaps, but Professor Bird’s lectures were the most in depth.

Learning about graphene and its drawbacks really helped me to understand the motivation for transition metal dichalcogenide (TMD) research. I appreciated the mention of transistors (especially field effect transistors) because they play a very big role in TMD research. I’d like to learn more about them!

Professor Aoki’s lecture, from Chiba University, was informative, but it was very research-intensive. Many of the methods he described were applicable to my research area, but it was a little hard to follow because there was a lot of technical information.

I especially enjoyed Dr. Lyon’s lecture, from the NSF Tokyo office, about our role as “unintentional diplomats.” It emphasized the importance of what we are doing here and reminded us of the impact of cross-cultural exchange. I was definitely inspired by her talk and really want to maintain the connections that I make here in Japan.

Return to Top

Week 04: First Week at Research Lab

When I arrived at the Iwasa Lab at the University of Tokyo for the first day of my internship, I wasn’t given much direction. I was quickly ushered through the experimental rooms before my mentor had to go to class, assigned a few shelves and desk space in the corner, and left to myself. I wasn’t sure what to do, so I read research papers until my eyes burned from excessive screen time. The exciting experiments that you think of when you hear “lab internship” are really only one part of the research experience. The deglamorized version was exactly what I saw: sixteen desk cubicles with graduate students hunched over their computers, typing away, occasionally getting up to print one thing or another.

I was eager to help and be put to work, but no one really knew what to do with me. It took me a couple of days to come to terms with physics research not being incredibly fast paced. It was something I should’ve expected, but it wasn’t until I was introduced to some of the processes that I really understood why. Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE), one of the focuses of my project, takes a long time. You need to wait for vacuums to bring chambers to low enough pressures, and then heat materials to incredibly high temperatures, turn this switch on, watch that gauge, turn this dial and watch that other gauge, make sure this meter doesn’t pass 5, etc. There’s a switch or button or knob for every step, and an exact order in which every step needs to be carried out. It’s a time consuming and careful process.

My mentor is Wang-san, who is a first year Master student from China. He’s been working with MBE for the past year and is very familiar with the process. He has a deadline to find an interesting transport property by the end of July that he seems a little stressed about. He’s still not entirely sure what to have me work on because many of the processes are time consuming and experience-based and he is working under a deadline. Right now the details of my project are ambiguous, but there is a pretty clear general goal: grow a material and characterize it. Most of my first week was spent getting familiar with the equipment and how it works, but I’m sure that the details will settle down more in the following week.

The other people in my lab have been very welcoming. All of them speak some English, so I’ve been able to have small conversations with almost everyone. Everyone is funny and interesting in their own way. One of the lab members, Kashiwabara-san has a superpower where he can add numbers together incredibly fast, like seeing ten two-digit numbers for 0.2 seconds each and adding them with 100% accuracy, fast. They invite me to get lunch with them every day and I try to practice my Japanese. I was able to have a short conversation fully in Japanese last Friday, which was a small accomplishment! In the lab, Japanese is the language everyone is most comfortable with, but everyone speaks English well enough.

One thing that was surprising to me was that there is a scheduled clean-up time every Wednesday morning. After the weekly Journal Club meeting, everyone goes to their assigned room and cleans. It reminded me of the video that we watched at the pre-departure orientation of all of the elementary school students cleaning up their school. Last week I was assigned to help with the office space and took out the trash with a couple of my other lab mates. When I told them that we don’t sort our garbage in the United States and they seemed shocked.

My housing was changed last minute to Higashi-Ojima, due to a leak that occurred where I was supposed to stay in Minato. Higashi-Ojima is a quiet residential town with lots of apartment complexes, families, and bicycles. I’m serious about the bicycle thing, everyone rides a bike in this town. It’s very urban, but it’s primarily a residential neighborhood. It’s definitely different from anywhere I’ve lived. It vaguely reminds me of residential areas in Silicon Valley. My housing is close to Higashi-Ojima station so it’s convenient to commute by subway.

Last week I also had the honor of not only meeting, but talking to and shaking the hand of Caroline Kennedy (!!!) at a reception for Fulbright Scholars. We were invited by Dr. Lyons of the National Science Foundation, who was one of our orientation lecturers. It was a surreal experience. It was the type of event that I only imagined happened in movies. Everyone was dressed smartly, drinking wine, introducing each other, and trading business cards. If you were done with your drink, you left it on a random table and someone would take it away for you. It was the type of event that made you recall all of the shameful things you have done as a college student and wonder how you ever became fortunate enough to get here– like surviving off a Costco 36-pack of Fig Bars for two weeks or thinking that adding Cheez-Its to your Easy Mac is a good idea. It was overwhelming and fantastic. I thought it really exemplified the range of experiences that the Nakatani RIES program allows us to have– to go from eating 7-11 food for breakfast to having dinner with the United States Ambassador to Japan all in the same day.

Overview of Orientation Program in Tokyo

With any type of move, there is always a transition phase. Moving from Sanuki Club to my lab housing was, for the most part, simple. It took a few days to get oriented and familiar with the area, but it was a lot easier than I expected it to be. I’m positive that this was due to having such a thorough orientation program.

The language courses taught me enough survival Japanese to not feel worried about not being able to ask for help if I needed to. The cultural seminars and activities gave me insight about things I otherwise might not have thought about. The technical lectures were incredibly helpful in getting me up to speed about my research topic. As a rising sophomore, I didn’t have a good understanding of band gaps or femtosecond spectroscopy before the orientation, so I found the lectures to be incredibly valuable.

One thing I found to be particularly interesting about Japan is amount of ritual that makes its way into everyday life– the seemingly unconscious “いただかいます” before each meal, or the instinctual “いらっしゃいませ” every time you enter a store. I’ve also realized how foreign I am to Japan, and how different American-Japanese are in general. Even with the younger generation in Japan becoming increasingly “westernized,” there are some fundamental cultural differences in what we value and the way we analyze things. I’ve noticed this through observation of strangers and interactions with the KIP students.

I’ve been trying to learn more kanji on my own, since it’s everywhere in Japan. I’ve been using an app called every day “Kanji Study” during my commute to lab. (I’d highly recommend it because it’s a great app!) After going through a set of maybe 20 kanji, I began to recognize certain characters everywhere. I’m beginning to be able to figure out what place names mean from their kanji. It’s satisfying to figure out that “東大島” means “east big island.” It makes me feel like a kid that’s learning how to read for the first time.

Research Project Update

Project Overview

I will be assisting my mentor in growing thin film transition metal dichalogenides (TMDs) by Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE) and later analyzing their physical properties using Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS).

Methods

There is a lot of specialized equipment required to grow and characterize TMDs. The growth that I will be specializing in is electron-beam growth by MBE. An atomic force microscope (AFM) is used to confirm sample quality and measure thickness. This is usually done before growth to confirm the quality of the substrate, and after growth to confirm the quality of the sample. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) is also used to examine the crystal structure of the samples. This is done after growth to analyze the sample. Electron beam lithography may be used if the sample is used to fabricate an electrical double layer transistor. PPMSs are used to characterize samples once quality film growth has been achieved.

Training

In the past week I have been introduced to most of the equipment and methods that I will need to use for my research project. A lot of it is very procedural. I was taught how to prepare substrate, generally operate the MBE machine, and use the AFM and XRD equipment. Doing XRD is definitely the most difficult out of all of the procedures. Part of it is due to a lack of understanding of how it works, but there are also just a lot of steps involved and it gets difficult to keep track of. I’ve spent the most time working with the MBE equipment, and I think I’m starting to get the hang of it.

Week 05: Critical Incident Analysis – Life in Japan

While there’s not a doubt in my mind that I’ve made some blunders in cross-cultural communication, no outstanding examples come to mind (especially outside of the lab). Almost every incident that I can think of has been a result of the language barrier, not cross-cultural communication.

I’m still far from fluent and often make mistakes when speaking Japanese. The only incidents of misunderstanding that I can think of are due to my inability to: a) understand what someone else is saying in Japanese, or b) express what I’m trying to say in a coherent way in Japanese. Sometimes errors that seem small to me, like pronouncing katakana words too closely to their English pronunciation, can make what I’m trying to say incomprehensible. Other times, I don’t know how to get my point across with my limited Japanese vocabulary. Usually with enough hand gestures these situations can be resolved quickly.

Another reason why I can’t think of a specific instance of cross-cultural miscommunication is because Japanese culture can be very non-confrontational. Even if I offended someone, or approached a situation in a culturally-different way, it’s not likely that someone would directly bring it to my attention. The mishaps of foreigners are also more easily excused, because people figure that we don’t know any better– which is generally true.

I, along with many of the other Nakatani students, have also been trying to follow the advice we were given in the pre-departure and Japan orientation. Every time I’m on a crowded train, I wear my backpack in front of me, to make room for other passengers. I did this on a train in Kamakura this past weekend, and one of the KIP students commented that she never wears her backpack like that. “Sometimes people look at you angrily, but it doesn’t really matter that much.” I was surprised to hear her say this, as I’ve seen many people do this on the trains and distinctly remember the phrase “Don’t be a turtle,” from orientation. I’d like hope that the reason why I can’t think of a critical incident is due to careful adherence to the cultural rules we were warned of, and not blatant ignorance. However, there is probably some instance that falls in the category of the latter.

I also don’t want to be quick to overgeneralize. There have definitely been a couple of things said by KIP students during discussions that I’ve questioned, but I don’t think that those specific opinions are reflective of Japanese society at large. Even with Japan being homogenous by American standards, there are many unique individual opinions that are not representative of the majority.

Question of the week

Typically, in the United States, scientists and engineers working industry jobs have more time off than those in academia. Is this also true of Japan?

Research Project Update

I think I had a clearer picture of where my research project was headed last week than I do now. At my welcome party with my lab, I was asked why I wanted to come to the Iwasa Lab. I replied that I was initially interested by their electrical double layer transistor (EDLT) work. My lab at the University of Hawai’i also uses the electrical double layer (EDL) phenomenon, but for a very different purpose. EDL phenomenon is a key part of the actuation mechanism that we use to electrically move liquid metal, whereas the Iwasa lab uses it for ionic gating in transistors. I was fascinated to see it used in such a different application and wanted to learn more about it.

“Oh, so you’re an electrochemist!” said Iwasa-sensei. I definitely would not self-proclaim that title. In my experience so far, my home lab’s focus is more on the devices themselves rather than the mechanisms that make them work. I have a general understanding of how an electrical double layer works, but definitely not that of an electrochemist.

They found my interest in EDLTs amusing, because similar to how my home lab’s focus is not electrochemistry, their focus is not devices. They mention EDLTs in many papers, but usually do so to demonstrate interesting physical phenomena in materials. However, one of the M1 students’ current research is focused on EDLTs.

The next day I was given copies of his work so far and told that he’d teach me how to fabricate an EDLT next week. I’m excited to learn more about them, and thankful that Iwasa-sensei is giving me the opportunity to. At the moment I am unsure of how much my project will incorporate EDLTs and material growth, as I was previously told by my mentor that two months is not quite long enough to focus on both.

This past week I helped a 4th year undergraduate student grow film in the molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) machine and read papers. I also shadowed my mentor using the atomic force microscope (AFM) and the x-ray diffraction (XRD) machine. To help me understand how to machines work and get more comfortable using them, I focused on documentation. I made a step-by-step guide with pictures detailing how to do MBE, AFM, and XRD. I also asked my mentor to look through it when I finished, to confirm that what I wrote was accurate. It helped me to internalize the order in which things are done and has made it much easier for me to use the equipment.

I spend a lot more time in the lab than I thought I would, but I really don’t mind it. On a typical day, I come in at around 10 am and stay until 9 or 10 pm. Everyone else stays for around that long, or longer; it’s crazy. The other lab members are all incredibly hardworking. We also have meetings every other Saturday. They’re progress reports about everyone’s research. I experienced my first one this last Saturday; it was about 4 hours long. After it ended, my mentor told me that they recently cut the meeting time in half, by having only half of the presentations, but making the meetings bi-weekly instead of monthly. Japanese work ethic is even more insane than I imagined.

Return to Top

Week 06: Preparation for Mid-Program Meeting

It is hard to believe that six weeks have already gone by. I’ve learned a lot since I got here, but there’s still so much more I want to learn before I leave. I want to improve my Japanese fluency and cultural understanding. I want to know at least 300 kanji before I get back. (I’m ~1/3 of the way there!) I want to learn more about my research project, and the projects that other members of my lab are working on. I want to understand more of the theory behind the work I’m doing– the interesting interplay of chemistry, physics, and electrical engineering in the field of material science. And of course, I want to spend time seeing more than just the inside of my lab office and the buttons on the MBE machine.

Outside of research, my biggest personal accomplishment at this point has been being able to decipher the meaning of place names written in kanji. I take the subway nearly every day and have gotten into the habit of studying kanji during my commute. It’s the perfect setting for it. It’s quiet (for the most part), there’s not much else to do, and you’re surrounded by the kanji that you’re learning. Many cities will have multiple stations, distinguished by directional or descriptive words. For example, there is 高島平駅, 新高島平駅, and 西高島平駅. 高 is the kanji for tall/high or expensive. 島 is the kanji for island, like in 東大島 (Higashi-Ojima). 平 is the kanji for flat. So a rough translation ends up being “tall flat island.” The other station names are modified by 新 and 西, which mean new and west, respectively. There are also certain kanji that appear in many place names, namely the kanji 町, which means town. Alone, this kanji is read as “machi,” but when included in place names it is often read as “cho.” This is one benefit to using station names to learn kanji, there’s always a romanized pronunciation available.

One of the biggest challenges I’ve faced is trying to improve my Japanese speaking ability. My lab mates speak to me almost exclusively in English, and I’m not fluent enough to jump in to their conversations in Japanese. They’re much better at English than I am at Japanese, so it’s easier for them to get their point across by just speaking English. All of my lab members speak also speak Japanese in casual form, so the polite conjugations that we learned in our language classes sound awkward and formal.

In the past week, I’ve been given a more solidified project, but it is very ambitious. I am to grow WSe2 by molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) and fabricate an electrical double layer transistor (EDLT) out of it. Last week I was shown the process of fabricating EDLTs, and read several papers and a report on them. There is still no clear timeline, but I am scheduled to have machine time with the physical property measurement system (PPMS) near the end of July, so there’s at least one hard-deadline for my device to be fabricated by. It takes about 2 days to grow film and test its quality, and 1-2 days to fabricate an EDLT. Theoretically a device could be made in one week. However, taking measurements by PPMS usually takes about 5-6 days. The biggest issue with my project is being able to get enough machine time, but I believe that it’s possible with the amount of time that I commit to lab. I have already been exposed to every part of the procedure for film growth and fabrication, so I think that it’s doable.

(Side note: I’m notoriously bad at cooking, so I’d be proud of making this meal anywhere in the world). – Sasha Yamada

Question of the Week

From talking to other students about their lab environments, I see what everyone was saying during orientation about each lab having its own subculture. By now I’ve realized that my lab is exceptionally hardworking, or “strong,” but there is a very lighthearted tone to this driven environment. We don’t have weekend BBQs like some of the other labs, but everyone jokes around with each other, and the hierarchy we were warned of isn’t very rigid at all. Some of the students even refer to Iwasa-sensei as Iwasa-kun, which was surprising to hear. How common is it for students to refer to their professors so casually?

Research Project Update

I’m becoming more independent in my lab environment. I’m being trusted with larger and larger tasks. I’ve been operating the MBE machine and preparing substrate by myself. I haven’t grown film entirely on my own yet, but I’ve done parts of every process on my own. I’ve removed samples from the load chamber, as well as put in new samples, unsupervised. I’ve taken atomic force microscope measurements, and initiated growth and annealing sequences for my mentor while he’s in class. He seems to be just as happy as I am with my newfound independence.

My eagerness and noisiness got me “captured,” in the words of one of the M1 students, by Suzuki-san, a D3 student who likes to teach. On most days I’m not given an immediate task to do when I arrive, so I try to keep busy at my desk until my mentor is ready to start a growth or measurement. One day during lunch, I mentioned that I wasn’t sure what I was supposed to be doing before my mentor arrives. The next morning, Suzuki-san asked me what my task was for the day, and when I said that I wasn’t sure yet, he offered to teach me how to fabricate EDLTs using the Scotch tape method. I knew what the Scotch tape method was from reading papers, but I hadn’t seen it in person.

I was excited to see what the other lab members were working on, especially because it meant going into the clean room. I geared up in an XL clean room suit and got to help prepare substrate and transfer MoS2 flakes onto it.

“This is a very primitive method compared to MBE,” I was warned. After manually searching for the “perfect flake” with an optical microscope for 20 minutes with no success, I conceded that it was a tedious process. It made me realize how significant it would be to achieve high quality monolayer growth with the MBE machine.

I’m happy to be learning a lot from my lab, and especially grateful for the opportunity to get so much hands-on experience. I have a feeling that the amount of responsibility that I’m allowed to have is uncommon, even for an internship like this. The sentiment of my lab mates seems to be to keep me as busy as possible in order to make the most of my time here, and I really appreciate that.

Week 07: Overview of Mid-Program Meeting & Research Host Lab Visit

The Mid-Program Meeting was a nice break from my rigorous lab environment. It was fun to reconnect with the other Nakatani fellows and compare the lab experiences we’ve been having. It was especially interesting to learn about the differences between the subcultures that arise in each lab, and the progress that everyone had made for their projects. Seeing everyone again also made me realize how much I’d missed their company these last several weeks.

It was also nice to see the Nakatani and Rice staff again. I felt that the debriefing meeting when we arrived at Kansai Seminar House was constructive because it gave us the opportunity to voice concerns that we may have been too unsure of to formally email about. The group setting of the discussion made it clear that there were some common concerns among us about our research projects, and living in Japan in general. It gave me insight into not only the many variations in our experiences but the overarching similarities, like living in a country as an obvious foreigner, or where we fit in as undergraduate researchers in labs of primarily graduate students.

I’m so grateful for everything he did for us. ~ Sasha Yamada

Horikawa-san’s generosity and excitement to show us real Kyoto definitely had the greatest impact on me. His love of and ties to Kyoto were apparent in the many activities he arranged for us. His family has been actively involved with Kamigamo shrine for generations, and because of his influence we were given a detailed tour in English, allowed to participate in a purification ritual, and actually allowed inside the shrine. It was incredible. Before we entered the shrine, the priest mentioned that foreigners had not been allowed inside for nearly 10 years. We were truly given special treatment in Kyoto.

I really enjoyed being able to experience the more traditional side of Japan in Kyoto. Everywhere in Japan has an interesting mix of old and new, but not to the extent of Kyoto. Tokyo may have Sensoji, which is beautiful and grand, but you can see Tokyo Skytree in the distance. Ginkakuji, in contrast, is flanked by a mountain and surrounded by trees. The steps are made out of stones, and the shopping street is isolated from the temple grounds. It’s quiet and peaceful in ways that you can’t replicate in Tokyo. We also got to experience (a shortened) tea ceremony. Even anticipating a lot ritual, I was surprised by just how much there was! There is a specific way to turn the cup when you receive it– twice counterclockwise– and the same follows for admiring the cup. Each matcha spoon has a name, and it often corresponds with the season. And of course, I can’t leave out the yukata! We were each, very generously, gifted yukata and geta and got to do hanabi (fireworks) in them. The yukata were absolutely gorgeous, and it was fun to see everyone dressed up.

One of the biggest challenges leading up to the trip was finishing my presentation for the Mid-Program Meeting. I started early, but didn’t submit it in OwlSpace until right before the deadline because of how many revisions I had to make. I originally started with a simple presentation, but when I showed my mentor he insisted that I make it as complicated as possible, to demonstrate the prestige of the lab. So I followed his advice and crammed tiny figures and tinier citations onto my slides. When I thought I was done, I showed Iwasa-sensei, who then told me that I should make it as simple as possible so everyone could understand what I’m doing. So I redid my presentation, again, and got a much better result than my first two drafts. Although it was a little frustrating to practically redo my presentation twice, I ended up with a better presentation and a deeper understanding of where my research fits in to the field of 2D material science.

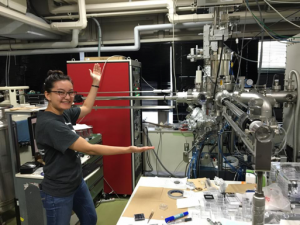

Host Lab Visit

When Kono-sensei visited my lab, I was surprised by his reaction. When I showed him the molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) machine, he looked at it in the same wide-eyed way that I had on my first day. To me it had looked like some complicated-space-vacuum machine you’d see in a scifi movie, but I assumed that it was a lot less impressive and intimidating to people in the field. I’d been using the MBE machine so often that I’d stopped looking at the whole machine and only looked for whichever dial or knob I needed. I’d forgotten how formidable it looked to me on my first day in lab.

More than anything, the lab visit made me realize how much I’d learned over the past two months. When I came to Japan in May, I could barely understand anything in the papers that I’d been reading. The only physics class I’d taken was classical mechanics and the words “band gap” were not in my vocabulary. But now, only two months later, I’m operating a MBE machine (another phrase that was not even in my vocabulary) by myself, and I have a pretty decent understanding of how the whole thing works. I’m still not able to understand everything in the papers that we cover in my lab’s weekly journal club, but I’m familiar with many of the procedures and machines that are mentioned, and I even have experience doing/using some of them.

Research Project Update

As I was in Kyoto for the Mid-Program meeting for half of this week, I was not able to get very much done in lab. However, while I was gone my mentor measured the AFM, XRD, and Raman spectroscopy of one of the TiSe2 samples we had grown the previous week and discovered that we had achieved very high quality growth. One feature that was especially significant was that we had achieved in-plane alignment because it was the first time we’d been able to do this. We spent the rest of the week (including the Friday of the lab visit) trying to see if we could replicate this growth. The pressure was significantly lower than our usual growth pressure when we grew the TiSe2 film, which may be why we were able to achieve such a good result. Unfortunately, after 10-7 Pa or so it is difficult for us to really control the pressure, ultimately making it difficult to accurately reproduce the same growth conditions.

The same trend as last week continues: I’m becoming more and more independent in my lab, and am also expected to do more on my own. The lab lecturer, Nakano-sensei, asked me if I had done a full film growth by myself yet, and insisted that I should when I told him that I’d done many parts of every process, but never the entire growth by myself. I am treated as much more advanced of a student than a rising sophomore here. It’s been a great experience so far, albeit a sometimes time-consuming and difficult one. Even with several weeks left of the internship period, I’m starting to feel the crunch of time. I’m excited to see how much I will be able to get done in the weeks to come.

Return to Top

Week 08: Research in Japan vs. Research in the U.S.

“Sasha, have you grown a film on your own yet?” said Nakano-sensei, the lab lecturer.

“Not yet, but I’ve done parts of every process,” I replied.

“I think it would be good if you did the whole process on your own,” (Notice the slight indirectness)

“Maybe you can come in earlier too and then Wang-kun can grow a film after.”

“Ehhhhh? Impossible! It would end at 9 pm!” said Wang-san, my mentor.

“Impossible? Why ‘impossible’?”

“I can’t do that! I would die. Too much!”

“Why not? I did!” said Nakano-sensei, smiling.

“Ehhhh???!”

Welcome to the Iwasa lab. This was a conversation that I had only a week ago that, in my opinion, embodies the spirit of the Iwasa lab. There are a few things from this short conversation that immediately stand out: there are very high expectations for everyone in the lab, I am given immense responsibility, and there is always an element of humor.

Like most laboratories in Japan, there is a specific culture that has formed in the Iwasa lab. This lab is especially “strong,” which means that the members are very hard-working and productive. On my first day I was given a handout with everyone’s picture and name and some text that explained that there were “no set working hours.” This didn’t mean that the hours are flexible and few, but more-so that it is not unlikely to find a graduate student sleeping on an arrangement of three office chairs when you get to lab in the morning– true story! My lab mates often arrive at 10 am and leave sometime after 9 or 10 pm, which is when I usually go home. They alternate between editing graphs, making devices, and recording data for hours a day, only sneaking away for lunch and dinner breaks in the cafeteria.

All of this time spent together creates a very tight-knit environment. Everyone jokes and eats with each other, and there is not a strong sense of hierarchy. This is one major difference between my experience and my expectations based on the talks given during Orientation. For the most part, everyone puts in a similar amount of time and work into their projects, so there is not as large of a distinction between a D1 and a M1 student as there might be in other labs.

Iwasa-sensei is also very actively involved in the lab. He is here almost as long as all of the graduate students. I feel that this type of leadership–by example–is a big factor in what drives the students to be so motivated and successful. He has a very good sense of humor and jokes with all of the students. He will frequently walk into the office and sneak up behind a student, and playfully comment on what they’re working on. He’ll then walk away laughing to the next unassuming student and grab a snack from the common area on the way. He’s well respected by everyone, but is also seen as more of a colleague than a superior. This relationship is best exemplified by many of the graduate students calling him “Iwasa-kun” instead of “-sensei.” It shows the closeness that they feel to him. From talking to other Nakatani fellows, this student-sensei relationship seems to be very rare.

I had previous research experience before the Nakatani program, and the experiences I’ve had here versus in the US have been very different. In the US, I similarly had a mentor that was a M1 student and worked with a mix of graduate and undergraduate students. However, my home lab is half the size of the Iwasa lab, with only 8 members total. Iwasa-sensei is also a lot more involved with students’ research than my UH professor (however, this is due to his many other obligations at the university, including being the EE department head). There is a lot more structure to what is done here. All of the B4 students are assigned graduate student mentors, whereas my UH research group had more undergraduate than graduate students, so most of the undergraduates worked more independently.

However, the biggest difference in my experiences has been the amount of trust and responsibility that I’ve been given in Japan versus the US. At UH, I wasn’t allowed to use much of our (limited as it is) equipment, and especially not without supervision. At the Iwasa lab, they want me to learn to use as much equipment as possible and become more self-directed. A more generalized example of this difference in trust is that in the Iwasa lab, we leave the experimental rooms unlocked, as long as someone is using it, even if they’re only checking on a machine every half an hour or so. At my UH lab, we always have to leave the door shut and locked, even if there are people working inside. This was something that was surprising to me when I first arrived at the lab, especially because their equipment is far more expensive than the equipment in my UH lab.

I have much more freedom and responsibility here, and for that reason I prefer this environment. Of course, the hours are much longer here, and I put in around 9 times the amount of time I would spend per week on my UH project, every week. I definitely wouldn’t be able to keep up a schedule like this during the semester, but it has been a very positive experience so far.

Question of the Week

After Japanese graduate students get their PhDs, do most of them pursue industry or academia jobs? Or is there no strong preference to one or another?

- Just like in the U.S., in Japan there are far fewer professor/academic researcher positions available each year and many, many students who apply for them. So, Ph.D. students in Japan, and increasingly in the U.S., must also look towards industry for career opportunities. In Japan it seems more common for a PhD student to plan to go to industry after their degree as compared to the U.S. where most students typically only focus on academic careers. Going into graduate school, its good to be open to both potential paths and know that there is no one right career track that all STEM PhD students should follow. There are lots of great resources out there about transitioning your PhD into an industry career and it might be interesting to look at what options this could provide you too.

Research Project Update

After the Mid-Program Meeting, I’ve been given a lot more independent tasks to do. The Monday after I got back, I grew WSe2 entirely on my own, from start to finish. When I got to lab, I measured the AFM of the substrate and attached it to a substrate holder at 10 am. Then, took out the previous sample and transferred my new substrate into the machine. I did our two-step growth process of monolayer growth, annealing, multilayer growth, and more annealing, and finished around 10 pm. It was a pretty gratifying experience because it felt like a mini-capstone project for my film growth experience. Unfortunately, that feeling was a little short lived because the quality of the film was not so great, but from the RHEED patterns that I recorded during growth, it wasn’t too surprising.

I’m trying to be more self-directed by preparing necessary materials without having to be asked to. It’s a reasonable assumption that we’re going to be growing film every day, so I’ve been starting to do our pre-growth procedures when I get to lab, instead of waiting for my mentor to get to lab and ask me to. This includes measuring the AFM of the substrate to check if the surface is suitable for growth, and then taking the best substrate and putting it onto a substrate holder. I’m still a little slower than the other students at doing this, so this process takes me around 2 hours to do. After I finish this, I can transfer the new substrate into the MBE machine and remove yesterday’s growth. All of these steps can be done without knowing specifically what film we will be growing that day. (We don’t always grow WSe2. My mentor is also working on metallic films and sometimes we are asked to grow different films for various projects.)

I feel like I’m not very focused on what my “assigned project” is (to grow WSe2 by MBE and then apply EDLT), but I’m doing a lot. I spend a lot of time assisting my mentor with his film growths and measurements. It’s all valuable experience, but might make it a little difficult for me to put together a cohesive poster presentation. I feel like I’m amassing loads of data, but from various side projects and it doesn’t all quite fit together. I’ve even been offered by another student to do a side project applying EDLT to Sm2CuO4, if I have the time. I’m stuck in a little dilemma where I feel like time is flying by, but I want to do it all.

Week 09: Reflections on Japanese Language Learning

The AJALT crash-course in Japanese during orientation was incredibly helpful because it provided me with a good foundation to build upon over the summer. However, I have not been able to build on it as much as I’ve wanted to. If I were to describe my Japanese learning curve for the summer, I’d say that over the orientation period it would look like an exponential function and would peak at the third week, and then start to plateau as my lab internship started, and eventually start to decay to where I am today. I’ve been doing some independent studying, mostly focused on kanji, but I haven’t been speaking Japanese as often as I thought I would.

On an average day I probably say less than 5 full sentences in Japanese, which isn’t very much. I communicate with my lab members almost entirely in English. The majority of them are very fluent English speakers, and my Japanese vocabulary is too limited for me to usually say what I want. I try to speak Japanese with the B4 students because their English is not quite as good at the graduate students’, but I don’t see most of them as often. I also didn’t have the option to take a Japanese class at my university because of my long lab hours and lack of communication with my lab secretary. I definitely would’ve liked to learn more Japanese than I have, but in some ways I sacrificed that goal to focus more on my project.

I have found that simple communication has gotten easier, and certain responses come more naturally. During the first few weeks, my Japanese language skills were clumsy at best. I didn’t quickly catch on to the social cues that are very apparent to native speakers, and the body language that we were taught to mimic in our AJALT classes always felt a little forced. Now I find myself doing the attentive head nod and “hmmmn!” noises whenever someone is talking to me, to let them know that I’m paying attention– something that seemed odd to do at the beginning of the summer. Or saying “いただきます” before a meal and “ごちそうさま” after. I’ve also gotten used to bowing to my lab mates from the doorway and saying “おつかれさまです” when I leave lab for the day, as they all do when they leave. There are a lot of non-verbal elements involved in speaking Japanese that are best learned through observation and repetition.

Many of the most challenging linguistic experiences that I’ve had were while talking to the B4 student that I’ve been working closely with for my project. Almost every single one of these encounters ended with us realizing that we were both trying to communicate the same idea, but had wrongly thought that we didn’t agree. In one case, we spent a good 10 minutes trying to tell each other that it seemed like we’d finished the current step of MBE growth and it was okay to go back to the office for a while. Kashiwabara-san thought that I said there was some problem with what we’d done and we couldn’t back yet, and I misinterpreted what he was saying as he thought there was a problem so we couldn’t go back yet. After a lot of hand motions and broken Japanese-English trying to figure out what the imaginary problem was, we both realized that there we’d misheard each other from the start. It was a funny situation, and we both learned to be more direct in future conversations about the MBE machine.

My experience in Japan, especially at Todai, has made me want to pursue further Japanese language study– or at the very least maintain what I’ve learned. I’m still deciding whether I think I’ll have enough room in my schedule to add a Japanese class next semester or not, but I plan on practicing Japanese with my friends that have been taking Japanese language courses. I’d love to be able to come back to Japan to do research again, but I’d definitely want to improve my language skills before doing so.

Research Project Update

The Iwasa lab work ethic is like no other. Monday was a holiday, 海の日 or “Marine Day,” but about half of my lab mates (and Iwasa-sensei!) still went to lab. I wasn’t sure if I was supposed to go or not, so I went just in case, but only stayed for 4 hours. My lab mates were worried that no one had told me it was a holiday, but I was concerned because they knew it was a holiday and were still in lab!

This week my research project started to become more focused. The B4 student that I’ve been working with measured his WSe2 EDLT, but wasn’t able to get very good results due to issues in device fabrication. He started to fabricate a second WSe2 EDLT and is scheduled to measure it later this week. Today the lab lecturer, Nakano-sensei, who has been helping me with my research project, assigned me a slightly different and big task for the week: to fabricate and take PPMS measurements for a MoSe2 EDLT. So I’m switching materials, due to the limited amount of MBE-grown WSe2 that we have available, but it doesn’t make too much of a difference because WSe2 and MoSe2 have near-identical properties. It’s quite a big assignment for only a week, but I’m excited to start fabricating a device. I should have transport measurements for this device by the next report.

My mentor has been working more independently on growing TiSe2, a metallic TMD, and has been getting very good results. One of the other M1 students, Matsuoka-san, will be helping me fabricate and measure my MoSe2 EDLT.

I’ve also spent a lot of time working on my abstract and starting to draft my poster for the SCI Symposium. I need to find a way to incorporate WSe2 and MoSe2 into my abstract and poster, but I don’t think it will be too difficult to do so.

Week 10: Interview with Japanese Researcher

I chose to interview my mentor, Wang-san, who is a M1 student from China. He is one of two Chinese graduate students in the Iwasa Lab. Everyone else is Japanese. He grew up in China and received his bachelor’s degree in physics from Huazhong University of Science and Technology. He became interested in physics in high school when participated in a Physics Olympics program and decided that he wanted to learn more about it.

He became increasingly interested in condensed matter physics and 2D materials while pursuing his undergraduate degree. In his 3rd year, he did a research internship about graphene at the Institute of Physics Chinese Academy of Sciences. He also focused on graphene when writing his graduation thesis.

He chose to come to the Iwasa Lab at Todai because of its reputation in the condensed matter physics community. He also explained to me that many Chinese parents encourage their children to go to school in Japan or the United States and save up money for them to do so. They believe that by going abroad, their children will have a better life than they would in China. When asked what he thought of the Iwasa Lab, and the differences between Japanese and Chinese research environments, he replied that Japanese researchers are “research-holics,” although he noted that some Chinese professors and post-docs are also like that. “They always talk about physics! Even during their free time, like at lunch!” he said, but then added, “Actually Pokemon Go has changed my opinion. Lots of people in Iwasa Lab play Pokemon Go now. I was surprised.” (Wang-san is currently the unofficial Pokemon Master in our lab because he’s got the highest level–14.)

His plan is to get his PhD, but he’s not sure what he’s going to do after that. He wants to stay in the academia, but believes that it is difficult to do so. He expressed interest in the possibility of going to America, but added that there aren’t very many American universities working on MBE, and they’re all very prestigious and competitive.

He said that the working environment in Japanese labs is similar to that of Chinese labs, but with more emphasis on rules. There is more structure to the hierarchy in Japanese labs, although he noted that the Iwasa Lab is unique with its absence of a rigid hierarchy. He also commented on our lab’s weekly cleaning assignments and trash sorting as being different. He’d prefer everything to be a little less strict.

We also talked about living in Japan as a foreigner, and how it can feel isolating at times. Especially in the Iwasa Lab, where the work is difficult and time consuming, he said that it is easy to forget to pursue your other interests and get lonely. He said that in China, lab members and friends will often go out to eat together, and their schedules are much more flexible. He feels that this is rarer in Japan and people prefer to go out in smaller groups. He wishes that students from other labs were friendlier with each other.

He enjoys living in Japan, but misses certain things about China. He especially misses eating breakfast at small shops and complains about not being able to find good breakfast food here. His plans for after he graduates are very open-ended right now, but he can see himself living in Japan, the United States, or China. “I’ve got too many options to think about right now,” he said. At the moment he’s too focused on trying to perfect his MBE growth process to really pin down his future career plans.

Research Project Update

This past week I fabricated a MoSe2 EDLT and took transport measurements by PPMS. I spent Wednesday re-measuring XRD for the MoSe2 film (I’d measured it wrong the first time by myself, but I got it right the second time), evaporating Ti and Au electrodes, etching lines between the electrodes with a micromanipulator, and applying a silicon ring for the ionic liquid with a tool made of copper wire, tape, and a toothpick. I was surprised by the number of steps involved in making these tiny devices, and especially the amount of direct contact I have to make with the sample. It is a difficult and precise process.

The next day, I attached my film to a sample holder and added the platinum gate. I then got to experience firsthand the joys of wire bonding– and spending an infuriating hour and a half trying to get one wire to bond only to realize that the machine wasn’t threaded correctly– I’d just assumed I was really bad it because all of my other lab mates had complained about wire bonding in the past. That concludes the fabrication process until you can actually measure your device.

On Saturday, (yes, Saturday) I measured the transport characteristics of my device by PPMS. The final steps of EDLT fabrication include applying the ionic liquid, and securing the platinum gate– both of which are much more difficult than I’d imagined them to be. The ionic liquid is applied by using tweezers and a tiny shard of glass. You dip the glass into the ionic liquid and use a microscope to get a single drop into the silicon ring on your device. It’s apparently okay to get some of the ionic liquid onto the electrodes, but it’s best to avoid doing so. Securing the platinum gate is a lot less forgiving. You can manage to remove all of the ionic liquid if you do it incorrectly–which I did– and if you bend the gate too much, you destroy its structural integrity and have to replace it–which I also did.

Thankfully the graduate student that was helping me, Matsuoka-san, was able to revive my device and we were able to start taking measurements. Everything was going well, until the measurements looked strange and there were peaks in places there shouldn’t be. So we took out the device and re-inspected it for any broken wires or glaring mistakes. We couldn’t find any, so we decided to try again and hope for the best.

Unfortunately, the best did not happen, and we had to take out the device one more time. This time we had the help of Nakano-sensei, who told us that two of the electrodes were broken, including the drain. We decided to switch one of the electrodes to be the new drain and measured a simplified version of the device. At this point, we’d been trying to start measurements for my device for over 9 hours, so we decided to leave it as it was and hope for the best.

And as luck would have it, my simplified MoSe2 EDLT showed ambipolar behavior! However, the current was too small (nA-scale), so I’ve made another MoSe2 EDLT this week. I started fabricating it yesterday and finished this morning– the process went much smoother this time.

Return to Top

Week 11: Critical Incident Analysis – In the Lab

“I think you take this NanoJapan Program too seriously! You work too hard!” Iwasa-sensei told me last week. (The Nakatani name hasn’t quite caught on yet in the Iwasa Lab.) I was definitely caught off guard by this statement. I know that I’d been putting in a lot of time into my project, definitely more than I’d anticipated, but I was only doing so because I thought that what was expected of me.=

“Oh, I’m just trying to make the most of my time here because I don’t know when I’ll have another opportunity like this again,” I replied.

“Sure, sure, but you are here until very late sometimes, and always come early!” he said. Now I was really confused by what he meant. Especially because this wasn’t the only time I’d heard comments about how much time I’d put into my project.

A few weeks prior to this incident, I’d been the first person in lab and Iwasa-sensei walked in and said, “Eh you are here so early! Good,” and smiled and walked away. It was only 10 am, so it wasn’t that early. Usually there are several others in the lab by 10. I was a little confused by this encounter as well, but he’d said ‘good,’ so I figured that I must be doing something right. So I just kept doing what I’d been doing, which was adhering to my somewhat crazy lab schedule.

The PhD students in my lab love to gossip. I’d gotten into the habit of eating lunch and dinner with them, so naturally I got to hear some of it. “Ah yes, Nakano-san said that he wishes Wang-san (my mentor) was here as often as you,” one of the D3 students giggled. They tend to pick on him a lot because he doesn’t always maintain the characteristic Iwasa Lab schedule, but I think he’s hardworking and reliable. I wasn’t really sure how to respond to that comment so I tried to change the subject.

All of the comments about me being in lab as often as I was had been positive for the most part, or at least subtly encouraging that I should keep working as hard as I had been. So Iwasa-sensei’s comment struck me as odd. I wasn’t sure if it was an offhand comment, or a more literal one implying that I should’ve been spending more time enjoying Japan and less time in the office. I know that I’ve spent a lot