Kenneth Lin

Kenneth LinHome Institution: University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Status: Sophomore, Expected Graduation Date: May 2020

Field of Study: Physics and Astronomy with a Minor in Mathematics

Host Lab in Japan: Kyoto University – Solid State Spectroscopy Group, Tanaka Laboratory

Host Professor: Prof. Koichiro Tanaka and Prof. Takashi Arikawa

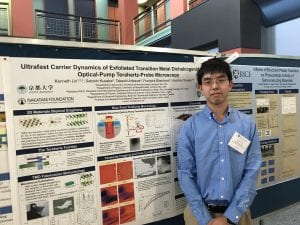

Research Project Abstract & Poster: Ultrafast Carrier Dynamics of Exfoliated Transition Metal Dichalcogenides with Optical-Pump Terahertz-Probe Microscopy (PDF)

Why Nakatani RIES?

As an aspiring scientist interested in language and cultures, I applied to the Nakatani RIES Fellowship for its balanced emphasis on intercultural learning with language training and intensive research through student exchange in Japan, a well-established leader in engineering and physics. As a Taiwanese-American, I found Nakatani RIES to be the perfect opportunity to more deeply understand Japan, a nation which has significantly influenced the development of Taiwan technologically and economically, and the role that its culture plays in driving scientific and societal progress. My interests and experience in astrophysics motivated me to apply for Nakatani RIES to expand my research scope into experimental condensed matter physics, a research area critical to developing the tools of astrophysics as the instrumentation and laboratory techniques rely on the multidisciplinary expertise of international teams of scientists and engineers. By deeply exploring the distinct yet interrelated field of solid-state physics, I hope to contribute diverse technical and scientific experience across different areas of physics as part of global research in nanotechnology, which will accelerate scientific advancement in interdisciplinary fields such as astrophysics.

Participating in Nakatani RIES would further my goals by building a foundation in experimental physics that would both complement and enrich my current work in astrophysics which relies on computational analysis. This focused training in experimental applied physics will enable me to broaden my research background to include an experimental emphasis as I work towards graduate school, leading to new opportunities for me to contribute in astrophysics-driven projects including telescope instrumentation research, which increasingly relies on interdisciplinary background in engineering, materials science, and nanoscale physics to develop. Furthermore, Nakatani RIES allows me to be directly immersed in international collaboration through exchanging with my Japanese peers and mutually sharing these experiences, a unique perspective in scientific collaboration that cannot be truly understood by merely observing from a distance. Becoming involved in an international laboratory would enable me to gain cross-cultural competency in a laboratory setting, a crucial skill only acquirable by experience that is necessary to thrive in the ubiquitous global nature of scientific research.

Goals for the Summer

- Grow my research experience in condensed matter physics, especially with instrumentation and experimental techniques

- Gain a deeper understanding of the cultural and interpersonal skills necessary to succeed in increasingly globally-connected scientific research collaborations

- Achieve essential conversational proficiency of Japanese and a broad understanding of professional Japanese in a scientific context

- Establish a lasting relationship with host laboratories, mentors, and Nakatani U.S. and Japanese Fellows

- Ride the Shinkansen and go to a railway museum

Meaning of Nakatani RIES Fellowship (Post-Program)

When I first applied to the Nakatani RIES program, I sought to experience research in Japan and its strengths in nanoscience to gain broader insight into how international collaborations in research shapes the cutting-edge of science. Coming to Japan for the rst time and with fresh eyes, I discovered how Japan has embraced culture and learned from others to advance its society for the betterment of a people. The countless UNESCO World Heritage sites in Kyoto echo the core of the Japanese nation and its history, a fertile ground for a millennium of intellectual inspiration. The meshing of culture, science, and art became clear during my time in Kyoto and I will long consider these months a formative academic and personal experience. Most science and engineering students do not have this opportunity to study abroad, let alone conduct research abroad, and I am deeply grateful to the Nakatani Foundation for providing this chance to stay in Japan for an extended period of time and carry out research in leading Japanese universities. My favorite experience in Japan was meeting and interacting with our counterpart Japanese Fellows. This unique group of peers also interested in international research allowed me to easily form strong relationships which I hope to extend far beyond the program.

Research Lab Overview

While I entered the Solid State Spectroscopy Group with minimal experience in condensed matter physics, the experimental work I carried out significantly inspired my interests in fundamental physics research as I came to realize the power of transferable scientific skills. This discipline of physics exposed me to the realm of optics, lasers, and their immense potential to disrupt current paradigms in materials engineering and scientific instrumentation. In the lab, I investigated the carrier dynamics of atomically-thin, single crystal transition metal dichalcogenides (TMD) using optical-pump terahertz microscopy. My work in this project was the first attempt in the world to image in the near eld a TMD sample within the terahertz regime, an effort defined by the uniqueness of our setup and instrumentation capabilities. The internationalism of the lab further made my time more vibrant as I worked alongside researchers from around the world, including a professor from Canada with whom I collaborated closely with on my project.

Although my work in this lab was related to solid state physics rather than my astrophysics where my research interests lie, I found connections between both fields that allowed me to grow as a researcher. Most notably, I was trained with critical experimental lab skills and tools including imaging analysis, Raman spectroscopy, and atomic force microscopy, techniques that I would not typically be exposed to in astronomical research. I gained a greater understanding of the background necessary to engineer new scientific tools through this training in experimental physics research, skills imperative for the development of astronomical instrumentation. My experience this summer has opened the possibility for me to pursue interdisciplinary work with experimental methods in astronomy through graduate school and career, using a theoretical objectives in astrophysics and experimental techniques of optical physics to inspire new innovation in space telescopes and imaging technologies.

Coming to work in the laboratory everyday was a true joy and privilege that I hope to continue in my career in physics. Not only did I have many students including undergraduate and graduate to consult with, but I most literally worked alongside postdocs and professors in a highly collaborative atmosphere. While the students were under no expectation to work the hours that they did, the hours and dedication that students invested into their research demonstrated that they truly enjoyed their work. Coming from a theoretical lab, I had little experimental experience but my graduate student mentor patiently guided me from material fabrication to analysis, checking in with me every step along the way. Both my host professors and graduate students with whom I received help from took valuable time out of their daily agendas to tutor me through operating instruments and running experiments. The general environment was entirely relaxed and my fellow lab members even remarked to me how “unique” their lab was compared to the typical Japanese lab, commenting how they themselves were likely the “liveliest” group in the physics building. In many respects, I concur with this self-assessment as it would not be unusual for half the lab to break into a conversation at any time. The lab group oftentimes resembled a group of friends who happened to have common research interests, where we would go on group lunches and dinners nearly everyday. I sincerely appreciate the warm group cohesion of my lab as it inspired a healthy work ethic balanced by a genuinely welcoming friendship.

Daily Life in Japan

The practical component of living in Japan was one of the most interesting and rewarding challenges that I have experienced even as I have spent significant time abroad growing up. Much of my life assimilated into a typical Japanese graduate student’s routine, where I spent a minimum of eleven or twelve hours in the lab building. I experienced a typical Japanese commute every morning, traveling by bus from Higashiyama-ku near Kiyomizu-dera to the main university Yoshida campus in Sakyo-ku. After the core morning segment of work, I would have a delicious meal at the North Campus cafeteria, food that I continue to dream of even after returning to the U.S. The workday would close with a group dinner at a local establishment, a practice that allowed me to try over twenty restaurants in the Hyakumanben area. Before returning home, I would always go the supermarket to buy the next day’s breakfast, either bread or onigiri. My love of railway transportation and experience with reading Japanese proved valuable on weekends when I had the opportunity to travel around the area. As a result, during my time in Japan, I have never taken the wrong bus or train and in the market, I have never unintentionally purchased a product as a result of language misunderstanding. Being able to navigate independently and run errands without much issue was a highly rewarding part of living in Japan. I was able to visit railway museums in Kyoto and Nagoya, in addition to eight World Heritage sites in Kyoto Prefecture, Lake Biwa, Nara, and Osaka. Climbing to the summit of Mount Fuji to witness the sunrise at the conclusion of my time in Japan was one of the most interesting experiences I have had that was a fitting way to close my time in the land of the rising sun.

Experiences with Japanese Culture

Living in Japan for the summer enabled me to probe deeper into Japanese culture than a brief stay would have revealed on the surface. Working with Japanese students allowed me to learn much more about their perspectives and as the summer progressed, I began to sense the subtleties of the culture. For instance, I learned much about how Japan views foreigners and tourism, especially relevant in Kyoto where tourists populate the many temples, shrines, and castles embedded in the city. My unique position as a student in the lab and as an international visitor allowed me to share the Japanese perspective of welcoming tourists for economical benefits while preserving the pristine state of important cultural properties. Visiting the many museums and historic centers of Japan, including the Tokyo, Nara, and Kyoto National Museums, and the Takasaki archaeological site enriched and informed my observations and interactions later on. While Japan has had historical periods of closed and open periods of foreign influence including in today’s globalization age, the Japanese people have a strong sense of national identity and have always kept their culture and heritage alive. Outside spheres of influence has only served to improve Japanese society where the most positive aspects of foreign cultures are extracted and adapted into their own lives. Recent history has shown how Japan successfully modeled its Meiji Restoration with the German-Prusso model of governance and incorporated the German culture of precision in which Japan takes pride in today with its high-quality manufacturing and emphasis on punctuality to name a few lasting impacts. This tradition of learning and adapting truly demonstrates how the Japanese society embodies societal progress that is culture-preserving and self-improving. This humanistic characteristic of Japanese culture has personally reinforced my idealistic goal to stay well-grounded in history and philosophy, and having values rather than economics guide my scientific career. Although difficult in the modern world of politics and interests where it is all too easy to become caught up in the technical scientific issues, I hope to keep my eyes trained on the big picture and to always humbly look forward to the future without losing sight of the past.

Before I left Japan, I wish I had… taken more opportunities to travel outside of my host city into the more rural areas in the country. Being in a city with high tourism activity, seeking a less trodden path would be a refreshing contrast.

While I was in Japan, I wish I had …. proactively spoken more Japanese to enhance my oral communication.

Excerpts from Kenneth’s Weekly Reports

- Week 01: Arrival in Japan

- Week 02: Language Learning & Trip to Mt. Fuji Lakes

- Week 03: Noticing Similarities, Noticing Differences

- Week 04: First Week at Research Lab

- Week 05: Cultural Analysis – Life in Japan

- Week 06: Cultural Analysis – In the Lab

- Week 07-08: Overview of Mid-Program Meeting & Research Host Lab Visit

- Week 09: Research in Japan vs. Research in the U.S.

- Week 10: Reflections on Japanese Language Learning

- Week 11: Interview with a Japanese Researcher

- Week 12 – 13: Final Week at Research Lab & Re-Entry Program

- Final Research Overview and Poster Presentation

- Follow-on Project

- Tips for Future Participants

Week 01: Arrival in Japan

The pre-departure orientation predominantly consisted of cultural and adjustment advice from past alumni and the program. Having lived abroad for a couple of years and with significant experience in international travel, the vast majority of this information seemed to cleanly summarize what I have personally already learned. While much of the information presented I have already abundant experience with, the opportunities to network with alumni and students based at Rice was a significant channel for me to meet like-minded students pursuing similar areas of research in physics and learn more about their scientific experiences in Japan. Meeting with the successful alumni of both the Nakatani RIES and NanoJapan program were highlights of orientation that were invaluable for gaining perspective into what opportunities participating in international research can lead to in research through graduate studies.

In some sense, the work ethic of Japan and the United States lie at opposite extremes. While in the U.S., each accomplishment in earned and deserved independently, there is a significantly tangible role of the group in Japan. Nearly every aspect of the Japanese culture can be traced to the collectivist center that dominates much of East Asian values. The values of effort, harmony, understanding, and form result from what seems to be the key core value of maintaining human relations, 人間関係. While this may maintain robust surface-level relations, this working style may potentially stifle creativity and critical thinking, especially on a humanities and sociological level. However, this type of concerted effort as a group towards a common goal also introduces benefits not observable in the U.S. For instance, in a scientific context, lab groups seem tightly-knit and work on fairly similar projects towards the larger goal of completing a research study or designing novel instrumentation. In visiting the labs at the University of Tokyo and speaking with the graduate students and fourth year undergraduates, I observed that within the group there was perceptible harmony that takes form as an “in-group” where members partake in activities beyond work on a regular basis. Maintaining the right relationships also includes observing well-defined hierarchy in Japan. This often means that the professor in the lab may seem more distant from the students whereas in the U.S., the professor of a group often treats their students as research colleagues. While this culture promotes excellent working relationships, it is often unclear what the underlying thoughts of others are and is a potential source of miscommunication. The emphasis on such honorifics and titles in Japan is a unique one where I have always found an interesting challenge. As another example, I was introduced to a researcher with a title of Assistant Professor, however when I addressed him as “~sensei” out of custom, the graduate students corrected me and reassured me that using “~san” for him is acceptable and even expected, a bit unusual but perhaps the case because of close age. This particular emphasis on titles, naming, and addressing are common characteristics that I observe every day that help Japan maintain a society that embodies harmony above almost everything else. While this is quite different from American values, this is certainly not my first time with emphasized “respectful” communication and thus, I adjust myself accordingly to maintain this sense of order and harmony.

Having been brought up in multiple countries, I may not necessarily embody only the American core values, but also have familiarity with how others may think. However, there are instances especially in Japanese class both in my home university and here when my investigative side insists on a more direct answer or a request of my own. While expecting direct responses to requests and questions is the norm in the U.S. where the people are generally more forthcoming and straightforward, even using a more direct tone with the Japanese tends to take them aback. While I have not personally experienced this myself as I have adjusted my speech and intonation to better fit Japanese cultural communication, I will continue to watch for potential areas where such Western values including independence and projected self-confidence can conflict with Japanese custom.

Having only lived and been to countries with right-hand driving, my first impression of Japan was the novelty of driving left-handed. Although I already knew about the traffic system in Japan, traveling along the left side of the highway and even walking on the left side of the sidewalk was a source of initial disorientation. Coming into Tokyo, I also noticed that the streets and sidewalks were impeccably clean—there was not a single trace of litter anywhere to be seen on the streets. While the layout of Tokyo with its many wandering alleyways were analogous to the city of Taipei in Taiwan, the key difference was the striking cleanliness of Tokyo. Although one of the largest metropolitan areas in the world, the cultural discipline has allowed to the city to remain in nearly spotless condition. Despite knowing that Japan has a cultural tendency towards impeccable cleanliness, I was certainly surprised and impressed that Tokyo is able to maintain this level of sanitation with the number of tourists that traverse its streets every day.

What may be most challenging in Tokyo is the lack of a strong public access Internet network across the city that has made it difficult to communicate with my lab groups in Japan and back home. Although I was informed of the lack of ubiquitous access to Internet in Japan by several Japanese students at UMass, I did not realize the extent of this until arriving in Tokyo. In nearly all major metropolitan areas around the world, public Internet access especially for foreigners have become a staple of the tourism industry. As a technologically savvy city, the lack of a public network system becomes more than a slight irony especially when cities including Boston, Toronto, and Taipei all feature abundant Wifi access points throughout the metropolis.

As a byproduct of small class sizes, Japanese language class is less structured and more personalized than what can be expected at a public or private university. However, much of the material to be covered I had already completed in Japanese class at UMass, which allowed me to use this opportunity to solidify my grammar and address any questions directly with an experienced Japanese instructor. I am using Japanese on a daily basis almost by default because I am always being addressed in Japanese. Instead of using English in return, I try my best to complete the exchange in Japanese, particularly in simple situations such as in convenience stores, shops, and restaurants.

The University of Tokyo laboratory visits were an important highlight of my first week in Japan. Not only was I able to visit the Tabata Lab for bioengineering and tour the UTokyo user facilities, but I was invited to visit the Shimano Lab for physics to extend my network by using my existing network. This experience was particularly valuable because the research area the Shimano Lab pursues is closely aligned with the research topics I will be studying at the Tanaka Lab in Kyoto. Since I have minimal experience in experimental physics and especially in solid state physics, being introduced to the research methods and instrumentation involved in this research area will be invaluable to my preparation for research at the Tanaka Lab. I was even able to meet one-on-one with Shimano-sensei in a meeting that lasted about an hour where he introduced me to his research interests, current developments in the field including the Higgs mode in low temperature superconductors, and their current work on seeking analogous behavior in higher temperature superconductors.

Additionally, I also found the Taiko drumming a particularly valuable experience to understand historical Japanese culture through a musical lens. As a musician myself, I found Taiko drumming to be especially relevant to musical evolution in Japan when the U.S. was not even discovered yet. The drumming was an outstanding hands-on experience that helped recreate the mindset perspective of traditional Japanese warlords when the country was not yet internally stable. The sumo wrestler talk was similarly a valuable introduction to a key surviving part of Japanese culture that provides us with a background prior to witnessing sumo wrestling ourselves. The Ikebukuro Life Safety Training Center visit was also an invaluable experience which introduced practical advice in the event of a natural or manmade emergency. I especially found the earthquake simulator to be significant as experiencing such a disastrous phenomenon allowed us to truly understand the magnitude of severity earthquakes can cost.

Finally, the Takasaki archaeological tour was another highlight of the week which provided an in-depth introduction to the ancient history of Japan, its elites, and their traditions. It was powerful to witness thousands of years of history that has culminated in modern-day Japan from keyhole-shaped burial mounds to square mounds. With the academic commentary from Professor Ken’ichi Sasaki of Meiji University, the visit was a comprehensive learning experience for me about the Japanese elites, government, and farmers. The political power wielded by landowner elites in Japan reflects a societal power structure that reminded me of pre-colonial Taiwan. From ancient history, Japan has always seemed like a stratified society and continues to reflect that today. Keeping this legacy in mind allows me to place cultural and historical context with current Japanese core values, such as a strict respect for elders, teamwork for a greater goal beyond the individual, and a united front.

Research Project Overview

This summer in the Tanaka Lab at Kyoto University, I will learn how to create monolayer samples of transition metal dichalcogenides (TMD), for instance with molybdenum sulfide, and measure its transmittance in the terahertz regime using the terahertz spectroscopy. While current research has investigated the THz transmittance of TMDs, the THz transmittance of single crystals has not been measured yet. By They also have unique optical and transport properties with the valley index, a new degree of freedom for charge carriers. This property opens a new category of ways to store and manipulate data called valleytronics. When electron energy is plotted relative to momentum, two deep valleys result and since ultrathin materials are sensitive to light, the valley can be controlled by incident light; consequently, if perturbed the two valleys can have unequal depths and allow electrons to have a preference for one of the two valleys. Monolayer TMDs are semiconductors with finite bandgap and are distinct from graphene which are semimetals which have no bandgap. While graphene has a high carrier mobility, the zero bandgap and thus cannot be “switched off” which effectively disqualifies graphene as a transistor. Two-dimensional TMDs however have emerged as a promising class of materials as they display a band gap with semiconducting properties similar to that of silicon, enabling the possibility of atomically thin transistors. Thus, ultrathin layers of TMDs have potential to serve as circuit components in fast electronics.

Week 02: Language Learning and Trip to Mt. Fuji Lakes

Week 02 Overview

The visit to JAMSTEC in Yokohama considerably broadened my insight into the Japanese scientific computing industry and in particular, its immediate societal applications with the Earth Simulator. As a highly seismically active zone, Japan combines its prowess in advanced electronics and expertise in geological studies to deep-sea drilling and creating earthquake monitoring areas that provide a warning system to the government should an earthquake source be detected. The ability of the marine vessels to drill deep through the Earth’s crust towards the mantle is itself a feat of engineering motivated by the potential to minimize the devastating effects of earthquakes as much as possible. Although the physical location of the supercomputing clusters was not accessible during this visit, viewing the cooling systems of the supercomputer facility allowed me to appreciate the vast magnitude of the JAMSTEC effort to push scientific and engineering limits for the benefit of those most vulnerable in the wake of natural disaster events. I have always been motivated by “science for the benefit of mankind” and the sophisticated and important mission that JAMSTEC undertakes was an inspiring time to reflect on the larger picture of how understanding fundamental physics has the potential to be of service to society.

The Edo-Tokyo Museum was one of my highlights of the week, dense with historical artifact and stories of how Japan developed socially and technologically. The numerous models, replicas, and exhibits demonstrated the extraordinarily rich history of Japan through the transformative Edo period and how Japan developed in the Meiji restoration. The immense volume of content and detail of the models and recreations enhanced my insight in how Tokyo developed to its current status as a global city. An important and overarching theme that reverberated through Tokyo’s history is its culture of education and learning, where literacy across all strata of society was nearly complete. Moreover, literature, schooling, and reading were heavily emphasized even prior to the entry of the Western spheres of influence. This systematic and disciplined way of life is evidenced today in the manifestation of modern Japan’s leading role in scientific and literary scholarship and is a testament to the vital role that a people’s culture plays in shaping its national standing. The Grand Sumo Tournament was a unique first experience of an ancient Japanese tradition that was a fitting segue from the history presented at the Edo-Tokyo Museum. I was impressed by the very stadium in which the competition was held as it seemed the arena was designed solely for sumo tournaments. This demonstrates the value that Japan places on the sport of sumo wrestling, particularly as a source of national cultural pride as the tradition makes a revival in today’s Japan. The orderly, procedural process in which each segment of competition was carried out demonstrated the importance that Japan places on its history and tradition. As a result, despite seeing a brief decline in popularity of sumo wrestling due to cultural shifts, sumo is experiencing a resurgence once again as Japan seeks to preserve and cherish its traditions. The amount of time spent watching the sumo wrestlers prepare for their turn in the competition ring far exceeded the total actual competition time and after the winner of each round was determined when either contestant was pushed to the ground or outside of the ring boundaries, it was very clear when the competition ended. Despite the substantial monetary stakes of this major tournament, the sumo competitors demonstrated deep respect for one another and reverence for the sport of sumo itself as exhibited by fair play and bows at the end of each round. It was at the sumo competition in which I truly witnessed the respect that the Japanese people place on their national heritage and culture.

The intertwined history of Japan and the United States as presented by Professor Sayuri Shimizu-Guthrie in the context of baseball, a vastly popular sport in both countries, was a unique perspective that I appreciated coming from a diverse background. Although the United States and Japan have undergone vast societal transitions domestically and internationally, the two nations mutually developed through common bonds such as sports. The United States for instance played a significant role in contributing to the Japanese system of education through educators who came to Japan and Japanese students studying in the United States. Prof. William S. Clark, the third president of Massachusetts Agricultural College, now UMass Amherst, established Hokkaido University in Japan. The considerable overlap between the two nations with respect to sport and their roots in education development demonstrates how increasing globalization in history has led to otherwise unusual shared pastimes. Although the rules of baseball are identical, I also learned that Japan has developed its own style of baseball in which the game is taken quite seriously compared to the U.S. where being an audience member of a game is a fairly laid-back and carefree experience. Even when new culture is introduced in Japan, there is always some amount of localization that occurs which allows Japan to codify its unique style and continue a long tradition of culture preservation.

Language Learning Experience

Japanese language class has mostly been a review of what I have already learned in my Japanese language classes back home. This continues to help me supplement my familiarity and proficiency with more advanced grammatical structures that are directly applicable in everyday lexicon. The Japanese language conversation proficiency evaluation that lasted a duration of more than forty minutes was one of the most substantial learning experience during these classes. Holding a content-driven conversation with a native Japanese speaker allowed me to practice increasing my rate of speech production, fluency, and accuracy. I was pleasantly surprised at what stilted Japanese I was able to conjure during this conversation, but when I was asked to describe my research in Japanese, I was only able to “katakanize” the technical English terms, which I am sure was more than halfway incomprehensible. Because I know this will not be the only instance where I may be asked to describe scientific terms in Japanese, I have made it a goal to learn how to give a synopsis of my research topic in Japanese. I hope to accomplish this during my time in the laboratory by attending journal clubs and using the language as much as I am able in the laboratory setting. However, I enjoyed my experience here especially as a Japanese language learner, it is often challenging to seek situations where I would be able to use the language in a more substantive context than the typical phrases used in daily life. Because survival language is used so frequently, I have not had too many difficulties in communication in daily life, since interactions with store clerks and staff are typically set phrases. I have felt surprisingly prepared for these interactions and has been one of the most interesting experiences in Japan. Learning a language in an area where the language is rarely even heard and applying my training in the global classroom of Japan is and likely will long remain a surreal and rewarding experience.

Mount Fuji Lakes Trip

We met the 2018 Japanese Fellows early in the morning as we began our trip to the base of Mount Fuji. While initially the two groups self-separated, we soon learned that the Japanese Fellows were actively interested in what life was like in the United States and this was the starting point for engaging in interesting conversations which began from university coursework and flowed into student life in Japan compared to the United States. After the first segment of travel, we arrived at the Oshino Hakkai Springs, a UNESCO World Heritage site with eight distinct spring ponds each with a symbolic enshrined deity. These ponds formed from the eruption activities of Mt. Fuji where crustal deformation caused the lakes in that were originally around the mountain to dry and become basins for spring water that continue to be replenished from the underground water stored within Mt. Fuji. The picturesque location and historical significance of these springs elicited conversations with the Japanese Fellows about the natural environment in the United States and what they could expect in Texas. Shortly thereafter, we toured the Kitaguchi Hongu Fuji Sengen, an ancient shrine dedicated in part to Mt. Fuji which was perceived as a form of deity itself. Once again, the respect that the people embody for Mt. Fuji is apparent through their traditional religion. These visits to shrines prompted conversations about religion in Japan and the United States over lunch. In one particular exchange, I learned that most of Japan was indifferent to religion which seems rather unusual given the high value Japan places on culture in which religion customarily shapes much as how Christianity shaped the early history of the United States with the initial settlement of the Puritans in New England. I was also told that the Japanese observe Christmas Day as a holiday where families are able to return home and reunite, which made for thought-provoking dialogue on how religion is viewed in both countries.

Afterwards, we proceeded to the Fifth Station of Mt. Fuji, the highest point reachable by vehicles. The temperatures even at the Fifth Station were more than ten degrees centigrade lower than that at the base of the mountain. Although conditions were overcast, it was clear why snow remains year-round near the summit. It was quite striking to appreciate the sheer height of Mt. Fuji, the icon of Japan, as we neared the Fifth Station and ascended the winding slopes of the road. After stopping briefly for photos and a visit to the souvenir shop, we headed to our hotel at the Gotemba Kogen Resort. While typically, a hotel may not deserve an extensive narrative, this particular establishment is worth expanding upon. We were welcomed by a large sign with wooden lettering “Blueberry Lodge, Welcome Friends!” After obtaining our room information, we entered the hotel only to realize that each “room” was a discrete hut in the shape of a circle, the setting of which resembled scenes from Peter Rabbit and Alice in the Wonderland. Beyond the complex of circular huts, there was an amusement park-like scene with a carnival-style carousel, an oversized bell, and cartoon character features from American film. After an abundant buffet meal that night, we explored the resort complex with the Japanese Fellows and watched an impressive water fountain light show located in this “carnival.” The eccentricity of this hotel was a moment for the U.S. and Japanese Fellows to bond in wonder of our accommodations. Later that night, I experienced the therapeutic benefits of Japanese onsen for the first time with the Japanese Fellows, of which further built our rapport with each other.

The next morning, our first stop was at the Numazu Deep Sea Aquarium where we were able to view the endemic marine species of Japan’s shores and sea. The Japanese spider crab, Macrocheira kaempferi, has the largest leg span of arthropods and was a major feature of the aquarium’s collection. I also found the various exotic deep-sea marine wildlife to be especially intriguing because of the sheer diversity of life that remains hidden in the depths of the Pacific Ocean alone. We had a seafood lunch adjacent to the aquarium where fresh fish, scallops, shrimp, and shellfish were cooked on grills built into the dining tables. Being next to a major fishing port, the seafood was extraordinarily fresh and only replicable at cities located by the coast.

The Mishima Skywalk offered a stunning panoramic view of the mountain ranges surrounding Mt. Fuji across the longest suspended bridge in Japan. Although slightly windy, the 400-meter bridge swayed harmonically in the air, serving as a live example of simple harmonic oscillation on a well-constructed bridge. Along the skywalk, the outlines of Mt. Fuji were visible in the distance as the distinct volcanic mountain that stands apart from the tree-covered companion ranges. After taking in the spectacular sights at the skywalk, we proceeded next to a local strawberry greenhouse where we had all-you-can-pick and eat strawberries. While some engaged in strawberry-eating competition, I sought to carefully compare the taste of strawberries in Japan to those grown in the United States. As I came to realize, the strawberries in Japan have a distinct sweetness that is reflected in Japanese strawberry-flavored beverages and desserts that I have always thought to be different from strawberry-flavored foods in the United States. In the U.S., it seems as though strawberries have slightly stronger acidic presence that enables the fruit to be carry a so-called “tangy” flavor, whereas in Japan the strawberries are smaller in size but have an increased density in the natural sweetness of strawberries. Only personal experience can fully bring appreciation to this distinction.

I had engaging conversations with nearly every one of the Japanese Fellows. In many senses, the approach to conversation with the Japanese college students mirrors my interaction with Taiwanese college students. Thus, I became comfortable with the Japanese Fellows fairly quickly and established warm rapport. In conversing with the Japanese students, I learned a few engineering students have similar interests to my own in aerospace and space systems, being involved in rocket-building clubs and fabricating propulsion designs, and I was able to share my interest in astrophysics with the future engineers who will build the next generation launch and delivery vehicles. On a social level, staying with the Japanese Fellows as roommates and participating in the onsen was one of the fastest ways to form bonds with our Japanese counterparts. I noticed that the Japanese Fellows were very patient and willing to speak proactively, which if based on the Japanese cultural values introduction we were given, would not be an expectation. However, I learned that many of the Japanese Fellows have had international experience and have outstanding command of the English language and thus have adopted an American-style demeanor when interacting with us. Their ability to adapt quickly to diverse situations and accommodate our lack of proficiency in Japanese was clear demonstration of the value they place on forming harmonious relationships.

Since half of the U.S. Fellows will be in the Kyoto and Osaka areas during the research period, the Japanese Fellows who are from Kyoto or are students at Kyoto University offered to remain in contact, a warm gesture that has made me feel welcome even before I arrive in Kyoto.

Question of the Week

Christmas is a Christian observance which must have rose from Western influence but has Christmas in Japan always been a commercial marketing holiday? As a generally non-Christian country, does Japan understand the history of Christmas and why it is observed? To extract and overlook the religious tradition behind a religious holiday seems to render the observance of Christmas to be merely a business-driven holiday meant to boost sales.

- Just like many aspects of western or foreign culture, Japan has a unique way of taking in various traditions and making them uniquely their own. For example, did you know that on Valentine’s Day in Japan women give chocolates to men? Only to receive chocolates from men back on White Day. And, the ‘traditional’ Christmas dinner in Japan is KFC? Also, the Tanabata Festival in Japan is actually taken from a Chinese QiXi or Double Seventh Festival? That being said, yes, Christmas is primarily a commercial holiday in Japan. However, the same could also be said of how Christmas is celebrated by many people in the U.S. and Europe today too… in spite of its religious roots.

- For more on this see:

- Festivals and Holidays in Japan

- Religion in Japan – Particularly the section on Christianity and Other Religions in Japan

- Christianity is one of the primary religions in Japan and there are churches where you can attend services year round. A number of past U.S. students have regularly attended church services in Japan as a way to reconnect with their spirituality and broaden their community/network in Japan. During the research internship period, you may want to seek out a church to attend to meet fellow Christians in Japan and talk with them more about the meaning of religion in their day to day life.

Intro to Science Seminar

The technical overviews of the scientific talks were most helpful and relevant to me personally because it enabled me to place the theoretical physics acquired from the classroom in the context of research and nature. Because much of the material related to solid state physics is somewhat foreign to me, having never formally nor informally studied the field myself as I am coming in from an astrophysics-focused background, being shown how the fundamental quantum physics principles are identical in the context of solid state and materials physics was reassuring. The applications of understanding physics here was also very helpful in motivating the research a framing a context for this work. For instance, both Professor Otsuji and Professor Saito of Tohoku University mentioned the relevance of solid state physics research across interdisciplinary fields including astronomy. In particular, I appreciated the connection that Professor Saito made to the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) interferometer in Chile, where the data analysis of each survey release is led by multiple research groups at UMass. The seminar by Prof. Otsuji primarily discussed the current research areas in graphene and terahertz sciences and was complemented by Prof. Saito’s discussion on carbon nanotubes. Prof. Saito also brought in mini-demonstrations with a slice of carbon with high thermal conductivity which cuts through ice surprisingly easily. These explicit demonstrations and graphic presented by the theory and realized by experiment was an important outlet for me to connect the theoretical and technical review of quantum physics from Prof. Kono to the frontier research areas carried out by Prof. Otsuji and Prof. Saito. With the introductions to terahertz technology, by experimentally studying and using terahertz spectroscopy in the context of solid state physics, I hope to be better prepared to contribute to the development of terahertz technology in astronomical applications.

I will be studying monolayer MoS2 and possibly related monolayer TMD materials yet to be determined. Such transition metal dichalcogenides exhibit semiconducting behavior much like silicon. The dimensionality of the material is 2D since it is one atomic layer thick. I will be primarily studying the optical and thermal properties of the material through terahertz spectroscopy. With special optical properties with respect to transparency, absorption, and refractive indices, in addition to high flexibility and high fracture strength, MoS2 is promising for applications with electromechanical sensors. TMD monolayers have applications in optoelectronics arising from their direct bandgap which is not present in graphene and in valleytronics, a promising direction for quantum electronics. While my mentor has mentioned that I will be learning how to make monolayer samples, and although I know the main methods of fabricating 2D TMDs are from CVD, MBE, and exfoliation, I am not sure what processes I will be handling in particular as I am awaiting to hear from my lab.

Week 03: Noticing Similarities, Noticing Differences

While Japan’s public transportation system may offer quite a different experience from a typical American public transport scheme, it is not uniquely distinct from the different public transportation systems that I have experienced. I will discuss the subway and rail network since that is the primary means of public transportation in the Tokyo metropolitan area. The most significant contrast from the subway and bus systems in the United States is much like the city of Tokyo itself, it is extraordinarily clean and orderly despite the vast number of commuters using the system during peak hours. The closest comparison I was able to make with the Tokyo Metro system is the Taipei MRT network. For instance, both systems discourage or limit food consumption onboard the train and commuters alighting the train are given the right of way during station stops prior to the boarding of passengers. When passengers stand, they are also facing the seated passengers out of respect on both sides of the aisle. People are courteous and yield their seats to those in need especially in the priority seating zones. However, during the rush hour such an immense volume of commuters use the subways that standing space becomes a commodity. Although the Japanese people typically keep to themselves and prefer minimal physical contact, the rush hour is a major exception where insistent and strategic pushing is necessary to get in and off the train at the right station. During the rush hour, riders carrying backpacks and bags are expected to either carry it front-facing or carry it rather in an effort to conserve physical space. However, during non-peak hours, it is acceptable to keep backpacks on backs; one consistent rule is to never place belongings on seating areas, since seats are almost always filled at all operating times.

The activities that commuters engage in on the run seem to be universal perhaps due to the ubiquity of electronic devices in the globalized information age. The vast majority from middle to advanced age riders are using their smartphones for various purposes. Occasionally there are those who choose to take a brief shuteye and passengers such as myself who venture to the very front or back of the train to admire the views of the tracks. There is minimal oral conversation onboard trains during non-rush hours although the rush hour certainly experiences a rise in volume. However, passengers do not eat or drink onboard the train; even if there are vending machines on the platforms, food is not consumed once inside the train. This habit is reminiscent of what is absent outside—Japanese people do not both walk and eat simultaneously.

The frequency of subway train operation is much greater in Tokyo than in Boston. On nearly every line during the daytime, the waiting time at the platform will be under one minute. As foreshadowed from the Japanese expectation for punctuality, the arrival times of the subways are impressively precise to the second to maintain the frequency of the trains. As a result of the expected precision timing of the public transportation, commuters need not be concerned about running late if time is properly budgeted. While everyone does walk with a purpose, I have not seen individuals frenetically navigating the subway system; most seated passengers do not even move towards the entryways of the train to exit before the vehicle is completely stopped. The order and discipline found even in seemingly chaotic situations is a unique aspect of Japanese culture that is visible from the public transportation system.

The Japanese rolling stock used for the subways and JR commuter lines are also remarkably well-maintained and updated whereas in the U.S., the infrastructure is generally dated and visibly in need of maintenance. On the Hibiya Line for instance, many of the rolling stock used were newly acquired from the Osaka-based company Kinki Sharyo, which is the manufacturer of the rolling stock used in the Boston MBTA Green Line and the Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART). Other common manufacturers include Hitachi and Kawasaki Heavy Industries. These subway cars are densely equipped with clear signage in at least three languages—Japanese, English, and Korean. In many cases, there is also Mandarin Chinese signage. The multilingual inclusion of public areas in Japan renders Tokyo one of the most tourist-friendly cities and is a sharp contrast to the transport system in Boston which is notoriously visitor unfriendly. The announcements are clearly enunciated in Japanese and English whereas with the MBTA commuter rail, announcements may not be made at all during rush hour. The robustness of the public transport infrastructure in such a dense city reflects the precision and discipline prevalent in Japanese culture.

These contrasts seem to reflect a balance of cultural and practical motivations. Many aspects of Japanese culture are driven by practical needs. For instance, maintaining cleanliness and refraining from food consumption onboard trains is a practical benefit that allows the metro system to remain spotless. Etiquette with regard to train boarding, yielding seats to those in need, and conserving space by carrying belongings are universal gestures that come from practical need. The level of quietness on trains in general however seems to be a product of the Japanese culture to be respectful. In consideration of other passengers especially during non-rush hours, the level of conversation is kept to a minimum. This type of considerate respectfulness is not necessarily abided by in other countries and may be attributed to the Japanese tendency to be quieter and more sensitive.

Orientation Program Overview: Week Three

To obtain a skyline view free of charge in Tokyo, head to the Tokyo Municipal Government building in Shinjuku. Rather than ascend Tokyo Tower or Skytree with masses of tourists, the government tower provides panoramic views of the Tokyo cityscape at 202 meters and this was where I headed on Monday afternoon. I entered towards the evening when the sun was slowly setting and set up a spot to take a time-lapse of the city transitioning to night. On the viewing floor, Tokyo Tower could be clearly seen in one direction and the Skytree in the distance in another direction. At nightfall, commercial airliners landing and departing from Tokyo Haneda International Airport could be seen in the distance with their bright beacons and landing lights. I waited about 90 minutes for the skies to reach the darkness of night and read some papers while the time-lapse was running. Although the process was gradual, the resulting footage was well worth the time investment. Building and tower lights slowly came on, the red taillights of vehicles on expressways became deeper in hue, and Tokyo Tower illuminated in a gradient of orange and yellow. To take in these views and how the city transitions to nightlife was a once in a lifetime experience that was somewhat surreal. On a clear day, Mt. Fuji can be seen from the observation deck and makes for an artistic juxtaposition of the world’s most sprawling metropolis with the sacred nature of the mountain ranges in the distance.

The cultural talks of this week presented valuable background into how the Japanese society behaves interpersonally and what the Japanese value in decision-making. The historical and philosophical perspective in the life sciences presented by Professor Emeritus Shinichi Nishikawa of Kyoto University combined the approaches of a humanistic narrative with a scientific lens. In particular, Prof. Nishikawa extensively discussed the significance of the information age and what potential is hidden in a time where information is readily accessible to a global audience. Although Prof. Nishikawa included substantial content on the evolution of science through philosophy, I cannot agree with his assessment that science is the sole means to define truth. While science may describe the mechanics of natural phenomenon, there is a finite limit in which scientific approaches are relevant. Science is not only driven by philosophy, but at scientific limits, philosophy takes over. Much like Moore’s Law, the more we learn about the science, the more directions we find and at times, we stumble upon very real and physical limits, most notably that of the speed of light and the arrow of time. The scientific method may yield some fundamental truths about the physical world but science especially in today’s domain of modern physics has reached crossroads where the truth cannot be appropriately constrained. The concept of truth is defined by its characteristic of being invariant, and as science is merely a methodology that facilitates the evolution of the human capability to describe nature, science cannot logically be the definer of truth. Nevertheless, Prof. Nishikawa posed several interesting and currently unanswerable questions of how information emerged spontaneously, how language came to be on Earth, and the next steps of neural networks.

The subsequent speaker, Mr. Kento Ito of INNE Japan Corporation, provided valuable insight into the history-rooted culture of modern Japan’s rich culture. He presented extensively on the cultural tradition behind kimono and Japanese tea ceremonies. Some particular methods of kimono-making for instance may take up to two years to complete and these products can become very expensive. Kimono can be crafted from a variety of ecologically-friendly materials as well, including banana tree leaves and wood. The lifetime of a kimono can also last more than one hundred years and reflects the emotional attachment that the Japanese place in a kimono that is passed across generations. After kimonos are worn out, they are repurposed as blankets, and after outlasting that use, are reused as cleaning cloth. Finally, the cloth of the kimono is burned, and the ash spread to catalyze the growth of hemp, the primary material of the cloth in kimono. Japanese tea ceremonies are also extraordinarily detail-oriented and rule-driven. Each step in preparing and serving tea is taken with concentration and precision for the sake of hospitality to the guests being hosted. For instance, when boiling water, one can only think about boiling water and when pouring the tea into the cup, the actual pouring is the only thought in the host’s mind during the process. These aspects reflect the spirit of Japan: valuing tradition, maintaining a disciplined lifestyle, and being precise.

Friday evening, Ozaki-sensei provided last-minute advice on Japanese behavior etiquette when interacting with hosts in homes and appropriate phrases for giving omiyage. There were some interesting cultural facts regarding price bargaining in the Osaka area and what phrase to use when attempting to negotiate for better prices. Being comfortable using honorifics for a diverse array of situations and using the appropriate word forms is an important part of integrating into Japanese society and Ozaki-sensei helped bridge that gap with this final presentation.

On my final Saturday in Tokyo before the research period, I finally had the opportunity to head to the classic and beautiful gardens of Shinjuku Gyoen. These gardens were formerly under the management of the Imperial Household Agency and now is a national park. The well-manicured lawns coupled with classic span bridges and an abundance of various flora was an interesting contrast to the background of modern buildings and twenty-first century technology. The gardens also featured the Shinjuku Gyoen Goryō-tei, known as the “Taiwan Pavilion” which was presented by voluntary Japanese in Taiwan in commemoration of the imperial wedding ceremony of the Crown Prince in the early Shōwa era who later became Emperor Shōwa. Japanese influence in Taiwanese history is also a major reason why the two nations share many similarities that I refer to in close comparisons. The greenhouse in the garden showcased the botanical diversity of Japan and even included novelties such as cacti and unique orchids. The pristine nature of the gardens in the center of an energetic downtown core reflects the insistence to preserve history and culture in the midst of economic modernization and commercialization.

The language program with AJALT concluded this week with speeches from every student on a free topic, in which I discussed byproducts of Japanese technologies such as the Shinkansen and the notable timeliness of international flights by Japanese carriers. Throughout language class, I have grown increasingly comfortable with employing oral Japanese for basic communication without rehearsing set phrases beforehand. While I have a sufficient vocabulary base to pass by everyday life situations, it was challenging to search in my mental dictionary and produce a comprehensible phrase. The language classes trained me to become more comfortable in speaking Japanese in unstructured circumstances and thus, I was able to confidently present my speech. However, expressing more complex ideas is a formidable challenge for me as I do not have adequate preparation to synthesize the various grammatical structures that I have learned and use them in appropriate ways. A challenge that I anticipate will arise is conversing informally in Japanese; I have only begun to learn about the Japanese informal forms and being able to aurally understand this abbreviated form will be the next hurdle to pass in my learning of Japanese. I hope to also further my vocabulary of kanji so that I approximate meanings based on radicals and context and read at a faster pace especially on public transportation. In expanding my kanji vocabulary, I hope to be able to express a general idea of my research in Japanese during my time at the lab.

Question of the Week

Why is some variety of potato salad included in nearly all types of bentos and set meals?

Introduction to Science Seminars

Prof. Stanton of the University of Florida provided a secondary introduction to semiconductors, carbon nanotubes, and terahertz spectroscopy. In addition, he introduced the background of pump-probe spectroscopy and femtosecond laser pulses. A macroscopic analogy that put the nanoscale world into perspective was imagining these experimental methodologies as stop-action photography, when Leland Stanford won a bet that all four legs of a horse are simultaneously in the air when galloping by capturing the motion of the horse over small time steps. Prof. Stanton also detailed some important and relevant applications of terahertz spectrum technologies to future electronics. For instance, terahertz radiation can be used in medical devices for imaging because the radiation is non-ionizing, unlike x-rays which are ionizing and may over accumulation result in adverse health effects.

The introduction to carbon nanotube synthesis technology from Dr. Don Futaba of the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science & Technology gave insight into the scientific pipeline and how fundamental research is linked to the industry through government-funded institutes such as this organization. The various methods of crafting carbon nanotubes were a completely new topic to me and I was surprised that there was still a less than precise understanding of how carbon nanotubes are fabricated. While the various methodologies of making carbon nanotubes may be well-known, exactly why a process succeeds was described as a “black box.” While it seems that scientific publications and the subjects of research become increasingly complex and sophisticated, it is pleasantly surprising to learn that oftentimes, many processes in intermediate steps or within the scope of a project is poorly understood. The work that Dr. Futaba leads in AIST addresses these issues by connecting the scientific laboratory to the scaling of novel material production. I also found Dr. Futaba’s personal anecdotes and background as a Japanese-American working in Japan to be relatable, as being educated in the United States and working in Japan is an experience that we Nakatani Fellows are gaining a short perspective of this summer.

The next presenter, Dr. Kunie Ishioka of NIMS, provided articulate insight into the status of women in science in Japan and her research in the ultrafast optical response of metals and semiconductors with pump-probe spectroscopy. It was concerning to learn that women in science, especially in physics, and most especially in Japan, still has a long way to go for equality and opportunity. The Japanese government has undertaken a few initiatives related to encouraging girls to explore STEM professions but as Dr. Ishioka remarked, the kawaii-styled posters may not be the best approach for addressing this disparity. Dr. Ishioka also noted that her birth year experienced an anomaly of a low number of children which she attributed to the long-held belief that during certain years of the zodiacal calendar that it would be more difficult for females to find spouses. Once again, the statistical correlation with these traditions demonstrate how the Japanese do indeed hold to these historic customs.

Return to Top

Week 04: First Week at Research Lab

On Sunday, we took the Nozomi Shinkansen superexpress to Kyoto Station to begin our work at the lab this week. Because my apartment lease does not begin until Monday, I spent the evening of arrival at the Kyoto Traveler’s Inn, where we will stay for the Mid-Program Meeting. Since no one from the lab planned to meet Janmesh and I at the station, we spent about fifteen minutes deciphering the Kyoto City Bus system and searching for the right bus to take to get to the hotel. The bus terminal at Kyoto Station is organized into different platforms; it may be worth considering studying the bus system beforehand to expedite the bus boarding process especially as the area in front of Kyoto Station is usually very busy.

The next morning, Janmesh and I set out with all of our belongings that we had in Japan and hauled it onto a bus to check into our apartment. Handling large pieces of luggage, let alone multiple pieces of them, was a true challenge on the bus, especially since most commuters, tourists, and students use the bus. When we arrived at the apartment, we waited for the agent to arrive for check-in. For the first and likely last time in Japan, the agent was quite late to our appointment time that I had to make a call to see if they were on their way. The rare and unusual lack of punctuality on this day affected my schedule for my meeting with Arikawa-sensei, for which I apologized profusely. With no time between finalizing our rental contract and heading to the lab, I was unable to present omiyage on my first day. However, when I brought my group gifts in the next day, they were gone so quickly I never had a chance to see it go. Omiyage-giving can be a delicate task in Japan, but it may be a good strategy to bring edible group omiyage first and then to individuals afterwards especially if pressed for time.

I began to work on my first day in the lab. I first participated in the weekly laboratory meeting with Prof. Tanaka and the entire lab group where I presented a self-introduction in English. Most of the lab members are able to communicate in English but since I am the only native English speaker currently in the lab, the lab members make an effort to use English around me, even to each other. My labmates seem eager to use English but that may also be because I respond in Japanese when possible if they ask a question in English to me. This two-sided effort seems to be a fitting process for the Japanese students and I to have exchange language learning. However, their command of conversational English is at a much higher proficiency level than my ability to handle Japanese. Nevertheless, I strive to continue my Japanese in at least the listening component. After the group meeting, a couple of the graduate students took me out to lunch at the Kyoto University shokudo, or cafeteria. The food in the cafeteria was some of the best food I have had in a dining hall anywhere. Even with UMass Dining ranked #1 in the U.S., I think Kyoto University has already bested that record. Because Arikawa-sensei had to teach a lab section for the rest of the day, I spent the afternoon with different lab members viewing and touring the facilities of the lab, which included four major lab spaces each with distinct purposes and instrumentation. Three of them were laser facilities, with pump-probe systems, a double optical parametric amplification femtosecond laser system, THz and Raman microscopes, and a host of sophisticated laser and cryostat equipment.

However, I was most intrigued by the materials fabrication lab, which they coined the ‘chemistry’ lab because it was where the materials being studied were made. There was an optical microscope that was worth the cost of several cars summed and an argon chamber for reactive chemicals. Since part of my project involves fabricating monolayer MoS2, I am looking forward to being in the chemistry lab. Afterwards, one of the lab members Takiguchi-san showed me his experiment with topological insulators in the terahertz regime, which are applicable in electronics used for secure communications. His description of every experimental procedure and part was clear and precise, and he kindly fielded all the likely trivial questions I had coming into solid state physics with little background. As he ran the experiment, I was pleasantly surprised to notice that the lab primarily uses the Igor Pro software for data analysis. I have used Igor Pro extensively in my lab classes and am comfortable with navigating its many powerful features. Having at least some experience with the analysis software used by the lab was particularly reassuring to me in an experimental lab as foreign to me as Japan.

That evening, the graduate students invited me for dinner in a nearby restaurant where we discussed what food we liked and what countries we have been to. My deskmate Tomoaki Ichii-san and Tanaka-sensei will be heading to France next week to present at a conference. Because this is a busy time for the lab with conferences, posters, and manuscripts being prepared, I was able to assimilate into the workflow of the group without being overly conspicuous. For instance, on my first day I was integrated into the cleaning rotations where different spaces of the lab were cleaned on Mondays, and I was expected to attend journal clubs and textbook clubs. This natural assimilation into the flow of labwork was a welcome surprise for me, especially when I was warned of being treated like an outsider or a perpetual guest.

My mentors are Kusaba-san, a doctoral student, and Arikawa-sensei, an Assistant Professor in the lab who conducted his postdoctoral work at Rice University. Arikawa-sensei picked me up after I checked into my apartment and guided me on how to take public transportation to get to the Graduate School of Science research complex, which is north of the main Yoshida campus. Everyone in the lab was welcoming and were eager to describe their research interests to me. Arikawa-sensei’s desk is located behind me, so I could always ask him questions as they arise. Kusaba-san is extremely knowledgeable on layered materials fabrication and he described the lab apparatus and how to use each piece of equipment appropriately on my first day. Since I have little experience in experimental methods, I appreciate the time he took to guide me through the lab. Other lab members were very warm too, and I participate in the group lunch and dinner nearly every day. Because everyone is in the midst of a project, we use mealtimes to get to know one another.

Within the lab, it seems that a combination of Japanese and English is spoken in the lab depending on the context. Japanese predominates in conversations while English is used as necessary for technical discussion. However, the lab members communicate with me in English because I have little to offer in technical Japanese, but I hope that I will be able to learn some aspects of my research in Japanese so that I would be able to give an overview if anyone were to ask. My lab mates seem interested in my background in that they always have some questions for me about my university life in the U.S. or about my involvement in supermassive black hole identification. We have even discussed my interest in railway transportation and for the first time, I heard that there are Japanese train fans that can identify the motor and manufacturer of a train based on the sounds. They have collections of train sounds; I hope to become more adept at identifying trains by only sound at the end of my stay in Japan. As my alumni mentor Julia Downing mentioned, the lab group goes to lunch with Tanaka-sensei, the Professor and head of the lab, and Naka-sensei, the Associate Professor, every day. At mealtimes, most of the students engage in lively Japanese conversations and it seems that there is little division between masters and doctoral course students as to each other, everyone uses the informal forms. However, my Japanese capability has no impact on my ability to carry out work in the lab, since I have numerous resources available and mentors who are more than willing to help.

My housing location is a reasonable distance from the Graduate School of Science, where I am working. By bus, it takes around 20 minutes to arrive at the closest stop to the lab and about ten minutes of walking. Kusaba-san lent me a bike, but I have not commuted by bike yet, so I have yet to find what the time is by biking. My apartment room is compact although perhaps more spacious than the rooms in Tokyo and is hidden away from the main streets. Although the location is on the same street as Kiyomizu-dera, it is very quiet and convenient to the bus stop, supermarket, convenience stores, and numerous kimono rental establishments. The facilities including kitchen and washrooms are shared by the tenants of the apartment building, but since I share two meals a day with the graduate students in my lab, I have no need to use the kitchen. Because our location is so close to Kiyomizu-dera, there are always large volumes of tourists around the bus stop and thus I hear foreign languages about half the time I am crossing that intersection. Since this area has so many foreign tourists, I would like to observe where these tourists come from and how the Japanese local residents view these tourists depending on which country they represent.

I have already begun to identify where these tourists are from when I took my first weekend to walk around the neighborhood for the first time and head up the hill to Kiyomizu-dera, with the souvenir shopping streets, street vendors, and kimono outlets. Nearly anyone wearing a kimono and the vast majority of tourist seem to speak Mandarin Chinese, with the Chinese tone indicative of China. There were also numerous students on school trips to the area, from elementary school age to middle and high school. The students are easily identifiable by their uniforms and are usually led by a few teachers. At the site of the entry torii, it seemed the only Japanese remaining were from the schoolkids and the shopkeepers. However, enduring the masses of these tourists brings the rewarding view of the Kyoto cityscape coupled with the ancient history of the temple. At this higher elevation, the entire city is visible, and it was apparent that the city was located in a basin, surrounded by mountains, suggesting a humid and hot summer ahead. This skyline contrasts sharply with the Tokyo view, which has towers of varying heights. In Kyoto, buildings are generally no more than ten stories in height, and the absence of electronic billboards and bright-light advertisements was palpable, a result of the city’s strict regulations on outdoor advertisements in the effort to preserve Kyoto’s scenery which is prized as a cultural asset. The setting reflects the history of Kyoto as the seat of power in Japan as the imperial capital and the cultural heart of Japan.

Reflections on the Orientation Program in Tokyo

The orientation program was invaluable for forming and cultivating connections with other Nakatani Fellows including the Japanese cohort. The opportunity to explore Tokyo’s many districts as a group was a bonding experience and was an essential time to really get to know one another prior to heading to our respective labs around Japan. I broadened my insight into the history of Japan by understanding how the past connects to the present day bustling cosmopolitan of Tokyo. The Japanese classes, while quite long, was a rewarding experience in becoming comfortable with spoken and colloquial Japanese. In my Japanese classes at UMass, I had already learned the grammar structures and vocabulary covered in the AJALT classes; thus, I was able to productively use this time to train myself in speaking more naturally. While I likely may never achieve fluency, gaining the confidence to do so was an important part of the language acquisition process. The most illuminating components of the orientation program personally were the Takasaki outing with Prof. Sasaki, the University of Tokyo visit, and the opportunity to spend a weekend establishing new relationships with the Japanese Fellows. These three core activities constitute the three key elements of why I am here: history and culture, leading scientific research, and forming new bonds and networks. Through these experiences, the link between how ancient Japan developed into a world leader in pushing scientific limits that remains a bastion of rich culture became increasingly clear and as I learned more, Japan became increasingly accessible as its society opened up before my eyes.

Although I had prior knowledge of Japan’s excellence in precision, whether in being extremely punctual or in manufacturing mission critical precision systems, I did not quite believe the magnitude of this culture until arriving in Tokyo. After examining Japan’s history more deeply, I became especially taken impressed by how Japanese culture has allowed it to make progress in a self-sustaining manner. Reflected in the many museums we visited and even in the ancient temples, the Japanese acknowledge that their approach of learning from the best of other cultures and adapting it in application to their own society is how Japan has advanced technologically and socially. Japan does not allow external cultures to overshadow its own traditions; instead, Japan searches for the best in others and learns by example. While in many nations, a culture may potentially be adapted in its entirety including the possible shortcomings, Japan actively seeks to extract what is worthy and embrace that as their own. As a modern example, Japan’s automobile industry skyrocketed after studying the superb mechanical designs of German automakers. Even from the early Meiji period, Japan’s readiness to learn from others and integrate the positive aspects into its culture while preserving its identity is an admirable national trait that continues to propel Japan forward.

Because coming to Japan and Asia was a new experience for most of us, during the orientation program, there was a tendency to attempt to go to as many different places in Tokyo as possible in the shortest amount of time probable. However, I learned that I would rather select a few places where I would like to go and spend a significant amount of time in deepening my understanding about that place. I find significantly greater value in truly appreciating something than merely having a superficial experience driven by near instant gratification. For instance, I could spend an entire evening admiring and observing the sunset and the awakening of Tokyo at night. I could also spend an afternoon in the exquisite environment of the Shinjuku Gyoen Garden. Spending more time on a few activities allows me to have time to think through what I am observing, ask interesting questions, and hopefully learn something meaningful from the conclusions drawn. Understanding a place, let alone a people, requires significant investment of time and thought; personally, living in the center of metropolitan Tokyo was much too commercialized and fast-paced for me. The comparatively quieter setting of Kyoto affords me the opportunity to think and understand. Although I have a language barrier, I hope to gain insight into how the Japanese think and the role that culture plays in cultivating behavior, especially with the honne and tatemae. I hope to accrue enough experience in interacting in Japanese to further appreciate its role in shaping relationships and preserving a culture.

Research Project Introduction

The scheme of my project is to make monolayer samples of MoS2 and transfer that to a crystal substrate LiNbO3, and then run terahertz experiments for characterization. In particular, we are interested in measuring the transmittance using the terahertz microscope. Since the special substrate has never been used with MoS2 and because the sample of MoS2 is difficult to target on this particular substrate due to its visible transparency, these steps may take longer to complete. After making at least a 10-micron square sample of monolayer on LiNbO3 substrate that is necessary for the terahertz microscope, I will begin the terahertz experiments. I will use standard mechanical exfoliation to fabricate monolayer MoS2 from the bulk material. Then I will use Raman spectroscopy to determine the layer number of the target sample by measuring the Raman modes and the frequency differences. I will also look for other few-layer samples and run the spectroscopic test to observe the relationship between the peak frequency, frequency difference, and thickness of the material in comparison with the values given by the literature.